Following the high-profile Pratt & Whitney engine failure over Denver in February, Japan Airlines has grounded the affected fleet.

Last December Japan Airlines had what seemed like a carbon-copy incident with one of its own Pratt & Whitney-engined 777s. An investigation on that incident was well under way, when the United P&W failure occurred. Both incidents followed another, nearly identical incident in 2018, also with United.

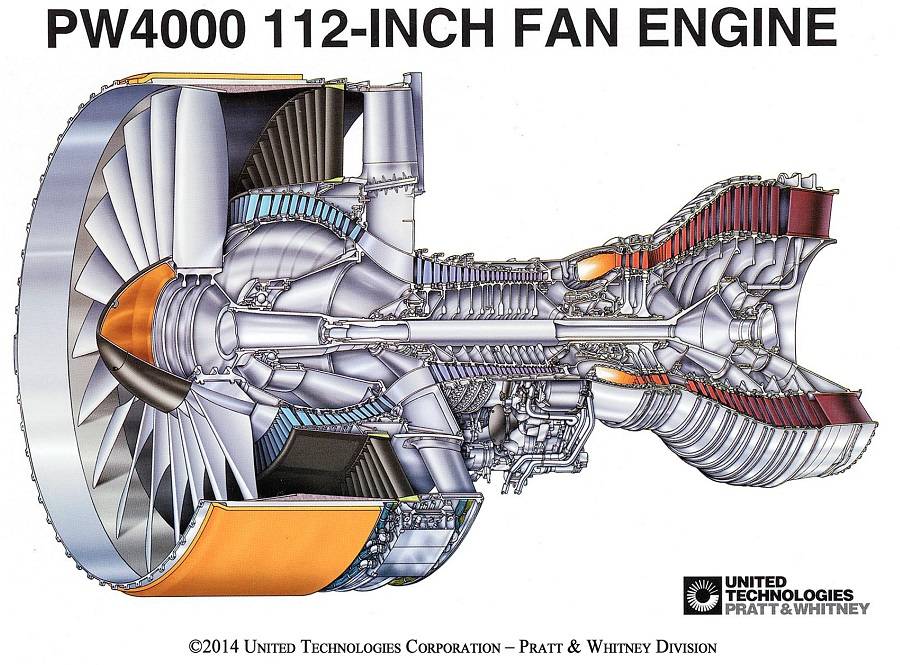

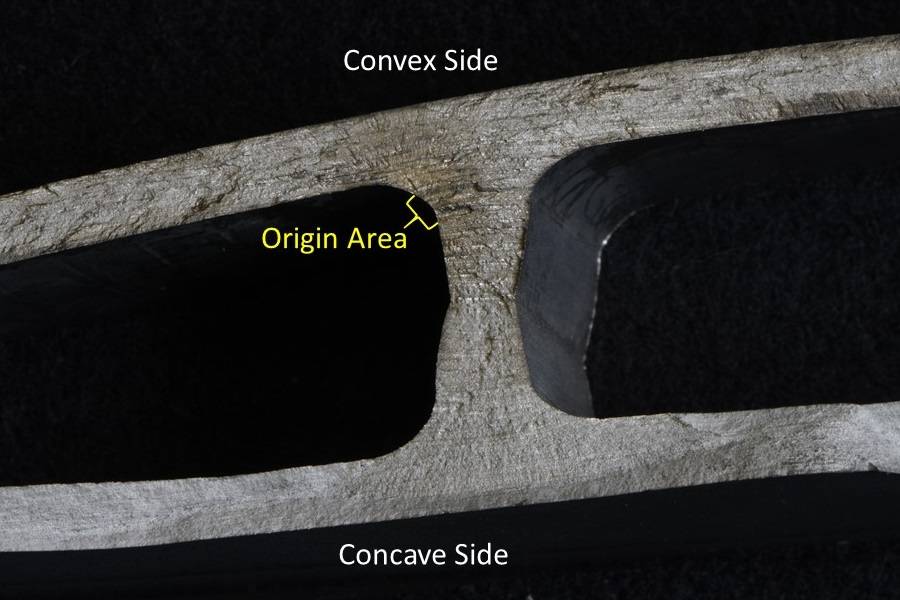

We have discussed these incidents at length already. If you missed them, United and Japan Airlines’ 777s had incidents where a fan blade in their Pratt & Whitney PW4000-112 engines broke in flight. The incidents happened in different phases of flight, however all three aircraft landed safely. There were no injuries. Only the earliest United incident has a final accident report at this time. However, it appears that all three incidents relate to fatigue cracking of the hollow fan blades.

While investigations on both the Japan Airlines And United Airlines Pratt & Whitney failures continue, airlines are pondering their options. The numbers of Boeing 777s that have these engines are relatively small. And more crucially, these planes are relatively old. JAL’s newest have delivery dates in 2007, although their date of manufacture is some time before that, in 2006. According to Reuters, they number 13 aircraft.

Pratt & Whitney Engines And Japan Airlines’ Fleet Plans

That number (13 aircraft) is hard to verify. This is because Japan Airlines had already put many of these Pratt & Whitney engined jets in storage. For many, this predated even the December failure. This was in part due to the crisis, but also because JAL planned to phase out the aircraft anyway. The one involved in the December incident was one of the oldest, at over 23 years old. After the United incident, Japan Airlines temporarily grounded any remaining 777s with Pratt & Whitney engines.

In its announcement, the airline explains that they previously planned to retire these aircraft in March 2022. This puts these early retirements to perspective. The FAA called for all users of these engines to ground their jets and get the engine blades inspected. Japan Airlines and all other operators have to send the blades to Pratt & Whitney’s facility in East Hartford, Connecticut. Other than JAL and United, affected airlines include ANA, Korean Air Lines, Asiana and Jin Air.

We don’t know at these point what discussions Japan Airlines may have had with Pratt & Whitney, regarding inspections/repairs. But it seems probable that additional checks would cost both in money and time. With that in mind, plus the pandemic, JAL’s decision to retire the planes early isn’t all that surprising. They have 17 GE-powered 777s (200 and 300ER) plus an ever-increasing number of Airbus A350-900s.

A Matter Of Usage?

The plan was to replace the 777s with the A350s and/or Boeing 787s anyway. JAL’s usage of these widebodies differs from that of many users. Most airlines wouldn’t worry about missing a few widebodies, in the pandemic’s immediate aftermath. But JAL’s aircraft do a lot of flying domestically, in Japan. So it will be interesting to see if they suffer a lack of capacity, in the next few months.

With Japan Airlines making this move, other users of 777s with Pratt & Whitney engines could follow suit. ANA plus the Korean users of the aircraft also employ them in dense medium-haul routes, at least in part. United doesn’t. Long-haul recovery could govern developments for them and some others. And of course this doesn’t mean that these aircraft will necessarily stop flying. There may be demand for them for future freighter conversions. However the one 777 conversion we know of (IAI), focuses on the 777-300ER, which has GE engines.

This certainly doesn’t have to be the end of these engines, either. Pratt & Whitney have been running them on Japan Airlines and many other aircraft for decades. The PW4000 family of engines is also powering many other aircraft types, both Boeing and Airbus. It appears that what’s causing these issues is a change in the inspection methods of these specific fan blades. Some newer engine designs now also use hollow blades, so there is a lot of interest in getting this right.

For more detail on the NTSB preliminary report on the February United incident, go here.

1 comment

Graham Stevenson

These blades were inspected following manufacture using a relatively new technique using both ultrasound and thermal flaw detection. The inspectors supposedly received insufficient training in the new technique and inadequate follow-up advice. Other jet engine manufacturers using hollow blades will need to examine their own inspection techniques. A hollow blade obviously can’t be entirely visually inspected.