The FAA will issue an Airworthiness Directive to ground older United Boeing 777 aircraft with a specific Pratt & Whitney engine model, for checks.

Two days ago, a United Airlines Boeing 777-222 experienced what looks like an uncontained engine failure. The aircraft was climbing out of Denver, performing flight UA328 for Honolulu. As it climbed through 13,000 feet, the inlet and cowling separated from the engine. More parts left the engine afterwards, causing a debris field over a nautical mile long. These parts fell in residential parts of Broomfield, Colorado, a few miles west of Denver. There was damage to houses and other property, but thankfully no injuries.

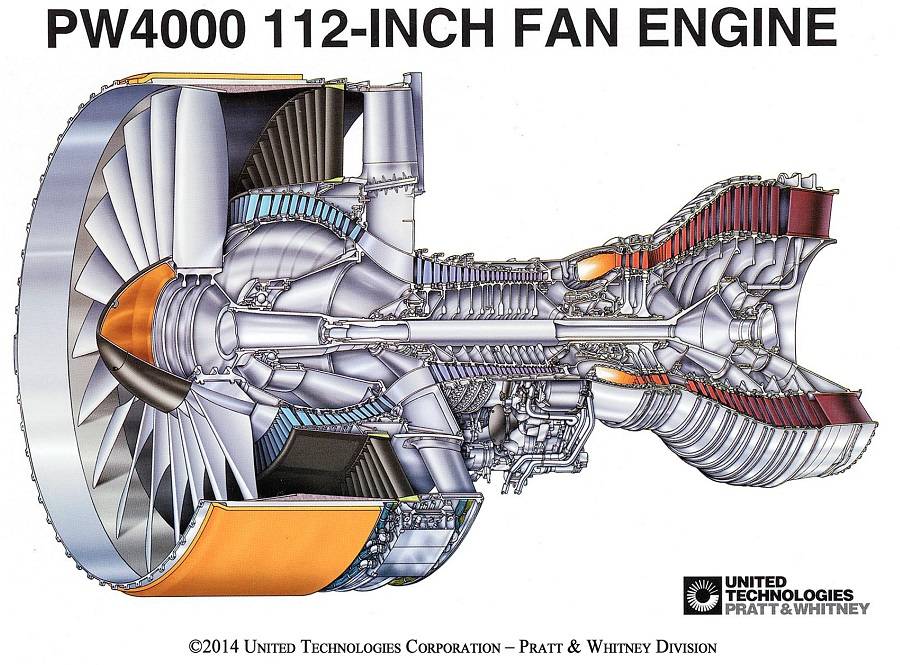

The incident caused reactions from the FAA, Boeing and several airlines. The FAA announced its intention to issue an Emergency Airworthiness Directive (EAD) involving 777s with PW4000-112 engines (112-inch diameter). This came after the NTSB reported that two blades from the engine’s fan disk separated. It’s early days yet, so the NTSB has still not confirmed how each blade separated. Their initial observations, however, seemed familiar.

One of the blades fractured near the root, while one next to it broke around the middle of its length. The containment ring, whose purpose is to contain as much damage as possible, had a portion of a blade stuck in it. Other blades had damage in their tips and leading edges, likely from other parts contacting them. The FAA now wants United to ground and inspect all 777s with these engines. United is currently the only 777 operator using the Pratt & Whitney PW4000-112 engines in the United States.

The FAA’s Decision To Ground United 777-200s With P&W engines

The FAA generally doesn’t rush to ground aircraft after incidents like this one with United’s 777. Not unless the plane is new. This Boeing 777 is certainly not new, at 26 years of age. But it is the third Boeing 777, with these Pratt & Whitney engines, to suffer such a failure. The most recent other example happened last December, as we reported, here. It involved a Japan Airlines (JAL) 777-200, in an internal flight over Japan. It also involved fractured blades in the fan.

However, in the JAL incident, the containment ring lived up to its name and largely contained the failure. Yes a cowling door separated, but the high-energy blade fragments didn’t pierce the sides of the engine. This wasn’t the case in the most recent United incident. It also wasn’t the case in an even older United uncontained failure, in 2018. It was the combination of these three incidents that caused the FAA’s reaction and decision to ground United’s older 777s. The 2018 incident involved N773UA, flight UA-1175 from San-Francisco to Honolulu. It happened shortly before the aircraft would begin its descent into Hawaii.

The NTSB has released its final report on the 2018 incident. It faults primarily the engine inspection process, which missed or misinterpreted signs of cracking, when the engine fan underwent service. The technician in question may have had inadequate training, while feedback between inspectors and engineers could be better. And crucially, Pratt & Whitney had changed one of the ways technicians can inspect engines during service, in 2005.

A New Inspection Process

The new process is Thermal Acoustic Imaging (TAI). United sent those engines for inspection back to the manufacturer (P&W). Here is what the NTSB report on the 2018 United 777 incident says – which could have played part in FAA’s decision to ground the planes:

“P&W developed the TAI inspection process in about 2005 to be able to inspect the interior surfaces of the hollow core PW4000 fan blade. P&W in keeping with NDI industry practice when implementing a new inspection process classified the TAI as a new and emerging technology and therefore did not have to develop a formal program for initial and recurrent training, certify the TAI inspectors, or have a Level 3 inspector on staff, as is done in other established NDI techniques.

“But in 2015, and still in 2018 when the incident occurred, P&W was still categorizing the TAI as a new and emerging technology after having inspected over 9,000 fan blades. At one point, P&W did provide training on the TAI, however, neither of the two inspectors were permitted to attend the training so that they could work to clear out a backlog of blades in the shop.”

FAA: Ground and Step Up Inspections Of 777 P&W Engine Blades

So, the process itself is not the reason the FAA decided to ground United’s P&W-powered Boeing 777s. As a new technology, the training for technicians and engineers in TAI inspections was still not formal. Two technicians who inspected blades relating to the 2018 accident, explained that they received 40 hours of on-the-job training. “In comparison, the certification requirements for the commonly used eddy current and ultrasonic inspections are 40 hours of classroom training and 1,200 and 1,600 hours of practical experience, respectively,” said the NTSB report.

Obviously, at this time it is too soon to say if there is a definitive link between these events. The FAA will ground all of United’s 777 with P&W engines in the US. Technically the process is an increase in inspections (step-up), not a grounding. However until the nature and scope of these inspections become clear, airlines will have to keep the planes on the ground. The FAA doesn’t have the authority to ground those outside the country. The Japanese aviation authority did the same thing. And now Boeing intervened, recommending the same action elsewhere:

“Boeing is actively monitoring recent events related to United Airlines Flight 328. While the NTSB investigation is ongoing, we recommended suspending operations of the 69 in-service and 59 in-storage 777s powered by Pratt & Whitney 4000-112 engines until the FAA identifies the appropriate inspection protocol.

“Boeing supports the decision yesterday by the Japan Civil Aviation Bureau, and the FAA’s action today to suspend operations of 777 aircraft powered by Pratt & Whitney 4000-112 engines. We are working with these regulators as they take actions while these planes are on the ground and further inspections are conducted by Pratt & Whitney.”

Another Coincidence!

After flight UA-328 was back on the ground in Denver two days ago, passengers boarded a different United 777-200. This was N773UA, the same aircraft that had the engine failure in 2018! The two aircraft had left the factory in Everett one after the other. Finally, it is worth pointing out that United won’t be left without 777s, after the FAA grounds affected aircraft. The grounding involves only the oldest of the 777s. Models after 2003 all have GE90 engines.

We also reported recently on the Longtail 747 incident, over the Netherlands. That 747 also has a Pratt & Whitney PW4000 engine. However that engine has a different fan: 94-inch diameter, instead of 112-inch. This has a different construction, without hollow blades. And the fragments we saw on the ground appear to be compressor blades, not fan blades.

There is a silver-lining to this story. In the NTSB report on the 2018 United incident, we saw that the failed blade went through inspection twice, five years apart. The first was in March 2010, the second in July 2015. In both cases, a technician ‘flagged’ the blade for further inspection. Clearly training and feedback got in the way… but the blade didn’t fail until eight years after the first flagging! This tells us that when properly trained, technicians will be able to detect problems well before a failure can occur.

5 comments

SN CY

@Andre T, correct. However, the un-contained part of the failure is also partly to blame on the airframe manufacturer, as they design the cowling. That cowling is never supposed to be punctured, let alone to fall off, but did.

It is supposed to be made to contain an explosive engine failure, which it didn’t do.

Dale Ferrier

Andre T, I agree, I read the BBC article about this today. They were quick to highlight that it was a Boeing airframe even though that has very little to do with the engines.

People are going to start developing an irrational fear of Boeing before too long because of this somewhat lazy journalism.

Certainly come here for reliable aviation news.

It did mention metal fatigue, which looking at the blades and other goings on, this certainly seems the primary line of enquiry.

Andre T

Thomadhansson people are placing this on Boeing but this is an engine manufacturer and to extent airlines responsbility. Airbus gets engines same places as Boeing.

Could two engines have this happen? Statistically not zero but sure it’s extremely low chance. One thing by this age of aircraft, engines will likely not have the same cycle life since engines are changed out for maintenance.

thomashansson

If it’s Boeing I ain’t going gets more relevant these days!

thomashansson

Isn’t it very likely that both engines could have the same cracked blades at the same time? And if so, the outcome of this could be 240 dead people? Everybody isn’t sully ‼️