With sanctions from multiple countries, can Russia still work with China to develop their CR929 widebody? What new challenges will it face?

Ever since its invasion of Ukraine brought international sanctions, some have argued that Russia could make its own aircraft. This would solve the stalled sales of Airbuses and Boeings – and the availability of spares for them. As we’ve seen, Russia already has programs for new aircraft, like the MC-21, a “Russified” Sukhoi SSJ and the turboprop Il-114-300.

But there’s a problem. Other than the Il-114-300 and the existing but older Tu-214, the other planes currently need foreign parts. Russia will eventually come up with Russified versions. But there’s also a scaling problem: Russia would struggle to produce these planes in the numbers it needs. That’s where China and the CR929 come in.

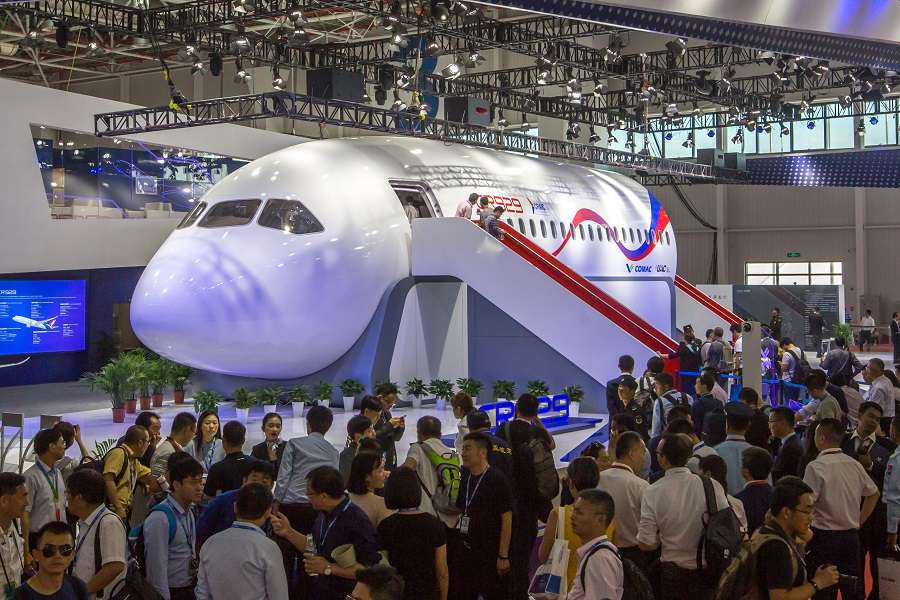

This aircraft design is a joint effort between Russia and China. The go-ahead for the project came over a year ago, with the two sides agreeing on their areas of responsibility in design and manufacturing. China and Russia created CRAIC, a joint venture between COMAC (China) and UAC (Russia).

The CR929 is a widebody aircraft, similar to the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787. The nine-seat-per-row plane will come in a number of different versions, seating anywhere from 240 to 440 passengers. Externally, some early mockups look eerily similar to a 787. And the instrument panel looks quite close to that of an A350.

A CR929 Redesign Without Western Parts

Of course, we’ve seen that UAC’s MC-21 relies on many of the same suppliers that Airbus and Boeing use for their jets. So some strong similarities, when it comes to systems, aren’t surprising. But that’s where the first issue appears. Like other new Russian and Chinese designs, the CR929, in its original inception, relies on western systems. And initially, western companies were keen to supply these systems.

The new sanctions mean that its designers will now have to modify the plane, to use Russian and Chinese systems. In itself, that probably isn’t an issue. Russia is working on “Russifying” the MC-21 and SSJ anyway. Since the CR929 is still years away from flying and entering service, its engineers should have the time to develop these systems.

And we haven’t mentioned engines yet. Again, the plan was to use western engines (GE, Rolls-Royce), at least to start with. There are plans to make an enlarged version of the MC-21’s Aviadvigatel PD-14 engines. But this is still on paper. The original target for a maiden flight for the CR929 was 2023. Even when western systems and engines were on the cards, this was ambitious.

We won’t expand on how enormous a challenge it is to create and certify such systems (and engines), since we’ve covered this for the MC-21 and SSJ-100. But it is a process that could take many more years. Plus, it’s unlikely that the designers of this plane will embark on designing such key systems before implementing them in smaller aircraft.

An Uneasy Partnership?

That still leaves the plane’s structure – and here, things are looking a bit better. Last November, we learned that a UAC subsidiary in Russia had started work on the first wing set for the CR929. The same company is making the composite wing and wing box for the MC-21. It is using out-of-autoclave technology, an interesting field that both Airbus and Boeing are also working on. But this is where the Sino-Russian relationship might see some… challenges.

We’ve seen that COMAC in China has been developing its own single-aisle, the C919. This plane is directly competitive with the MC-21. The Chinese plane is simpler in its design and material choices, while the Russian plane is more efficient. But arguably, the C919 has a bigger domestic market to look forward to, than the MC-21. However, if Russian carriers can’t buy Airbus or Boeing, the MC-21 may have better prospects.

But the problem, when it comes to the bigger CR929, isn’t a competition between the new partners. We saw that western companies (and governments) were concerned when it came to technology transfer to China, in the C919 program. There were even some allegations of industrial espionage, including several arrests.

CR929 Technology Transfer And… Destinations!

Russia has also been somewhat reluctant to share some key aviation technologies with China. This has been the case, especially with some military aircraft designs, that China bought and then copied. So it remains to be seen how well the partnership will work when it comes to the CR929. So far, UAC in Russia looks set to design the composite wing and wing box, engine pylons and landing gear. However, that doesn’t necessarily tell us where these parts will eventually be manufactured.

Finally, we get to the newest problem with this aircraft, which is likely making China, in particular, a bit nervous. And this is where this plane will actually fly. Russia and China will not only have to design and build the CR929. This isn’t an MC-21 or C919, that could operate domestically just fine. It is a long-haul aircraft and its operators will want to fly it to international destinations.

And this means that foreign countries will need to recognize/approve the plane’s Russian and/or Chinese certification. In turn, this means that the engines, avionics and other electronics, landing gear and the design of the CR929 itself, will have to satisfy foreign aviation authorities. In the present climate, this sounds rather difficult, to put it mildly.

EASA in Europe has revoked the certifications of multiple Russian aircraft, including the SSJ-100. More recently, the European Commission banned 21 Russian airlines on safety grounds. As we saw, this was because the Commission was unhappy with their actions, i.e. flying aircraft without airworthiness certificates and/or insurance. But the Commission also castigated Russia’s aviation authority, for allowing this to happen.

An Uneasy Future?

So will EASA, the FAA and other aviation safety bodies accept a Russian certification for the CR929? Or would they accept China’s certification, if the plane uses Russian systems and components? Note that the trade situation between China and the US is already somewhat strained – again, to put it mildly.

So to recap… UAC and COMAC need to validate the design’s structure. Then the CR929 needs a lot of key Russian and Chinese systems that currently don’t exist because they’ve both been buying them from abroad. This includes engines, of a class/size that neither country currently has. Then, the two countries have to certify these systems and convince other countries to let the jet land at their airports. Or, they’d have to accept that it would only operate between Russia and China.

China has reportedly been unhappy with Russia’s strained international position, since the invasion of Ukraine. The CR929 is just one example of a joint project that has a questionable future, as a result. Like Russia’s MC-21, this widebody seems to incorporate features and technologies that make it an interesting jet. But its success, both commercially and in its manufacturing, now seems that much more uncertain.

3 comments

[email protected]

2025 is long time ahead, the Chinese and Russian will develop their own planes in these 3 years lightning fast as they need far lower security levels and can be much cheaper.

dirk

Not so sure. Suppose the American president will not be Joe Biden or Kamala Harris in 2025, the new Republican president will probably lift sanctions on Russia, thereby giving Boeing renewed access to the Russian market.

[email protected]

Boeing and Airbus will loose that market for ever!