It started as a bomber project, but the XB-70 Valkyrie very quickly became a research vehicle for USA’s Supersonic Transport (SST) program!

We recently had a look at the history of the Lockheed SR-71. Not only was this aircraft remarkable in its own right, but it also greatly expanded the use of titanium in aviation. Even so, no aircraft coming after it even needed as much titanium as the SR-71. As we saw, its fantastic speed was a key reason why the SR-71 needed titanium to such a large extent.

But the SR-71 and the A-12 that preceded it weren’t the only Mach-3 capable jets to emerge in the 1960s. The XB-70 Valkyrie had its first flight in 1964, a few months before the SR-71’s first flight! But relatively few people know of this enormous aircraft and its role in aviation. And that’s a shame because the plane’s utility was both military and civilian/commercial.

But first things first: what was it? The plane’s name is a clue. In US military nomenclature, aircraft types with a ‘B’ prefix are Bombers. An ‘X’ before the ‘B’ denotes an eXperimental variant. So the XB-70 Valkyrie was an experimental variant of the then-forthcoming B-70 bomber. Except… it wasn’t. When production of the first XB-70 got the green light, the plans to introduce a B-70 bomber were already cancelled.

XB-70 Valkyrie – A Research Program

The USAF had actually cancelled those bomber plans about three years earlier. The reason? Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). The plane’s critics pointed out that it made little sense to use even a really fast bomber, instead of missiles in silos. However, enough development work had already taken place, to convince the government to keep the program alive.

So North American (the manufacturer) eventually got the green light to make the XB-70 Valkyrie – actually, three of them. Further cuts meant that only two of them ever flew. In terms of design, the Valkyrie is unique, with the tips of its delta wing hinging downwards at altitude. This was because it used compression lift, taking advantage of shock waves emanating from the engine intakes! The feature also moved the centre of lift forward, eliminating the need for trim tanks.

Also, the XB-70 Valkyrie was a big aircraft. The SR-71 was 32.7 metres (107’ 5”) long. The Valkyrie was 56.4 metres (185 feet) long. For comparison, Concorde’s length was 61.6 metres (202’ 4”). This made the XB-70 an appropriate size to study future supersonic transport (SST) aircraft. Note that this plane flew about four and a half years before Concorde.

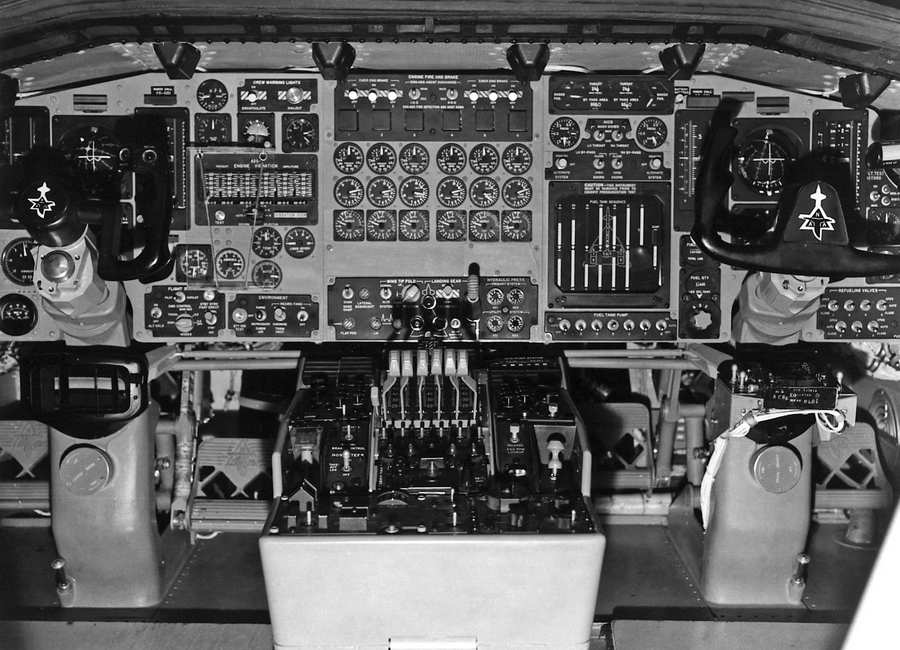

Interestingly, the operational B-70 would have a Concorde-like drooping nose on landing. The XB-70 Valkyrie had the same twin-windshield layout. However, all available photos seem to show the Valkyrie test aircraft taking off and landing with the nose up. So it likely wasn’t operational, for these test aircraft.

Materials For Mach 3 Flight?

But perhaps it is the construction materials of the Valkyrie that are most interesting, in terms of its SST-specific testing. The United States launched its own SST, Boeing eventually winning the contract to develop its 2707. North American also took part, using many design cues from the XB-70 Valkyrie. But the point is that the United States didn’t want to simply match Concorde’s Mach 2.05 cruising speed. The US wanted to go for Mach 3. And with a bigger aircraft.

Higher speeds meant more exotic materials. This is a topic we will examine more closely, in a future article. But as we saw with the SR-71, aluminium doesn’t work well beyond a certain speed. The SR-71 used titanium. The USSR’s MiG-25 used steel. And the XB-70 Valkyrie? Why it used both steel and titanium!

More specifically, the XB-70 used a steel honeycomb skin for the majority of its surface. Titanium was the material of choice for the leading edges, plus other areas that got hotter than the rest. Even after Boeing continued as the only choice for the American SST, NASA’s XB-70 Valkyrie test program provided valuable information. The plane’s six engines also gave engineers valuable data.

Loss Of The Second XB-70 Valkyrie

Sadly, one of the two test aircraft had a tragic mid-air collision with a Lockheed F-104N Starfighter. The pilot of the small fighter misjudged his plane’s distance from the XB-70’s wing, behind and below him. Eventually, he got too close and the aerodynamic forces from the enormous plane flipped his aircraft, hitting the bomber. The fighter immediately became a fireball, killing its pilot.

The XB-70 Valkyrie lost one of its two vertical stabilizers, the second one also getting a lot of damage. Eventually, the aircraft became unstable, lost altitude and crashed, killing one of its two pilots. The other pilot managed to eject but suffered serious injuries.

As a test program, the XB-70 provided a lot of useful data to both USAF and NASA. The original steel honeycomb panels suffered some damage at Mach 3, leading to improvements. The aircraft also tested concepts like the use of fuel as coolant – something the SR-71 was also doing.

Some data from the XB-70 Valkyrie program found use in more recent military aircraft, like the B-1 bomber. But ultimately, the impressive design didn’t lead to an American supersonic airliner. Boeing’s 2707 SST eventually stalled, going nowhere. Technology limitations, a negative public perception of supersonic jets and perhaps the over-ambitious specifications, killed the project. But arguably, the business case for supersonic passenger travel was rather questionable.