Last Sunday (the 11th) saw Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson go into space, with 5 more people. But did they really do it? Well, yes… and no.

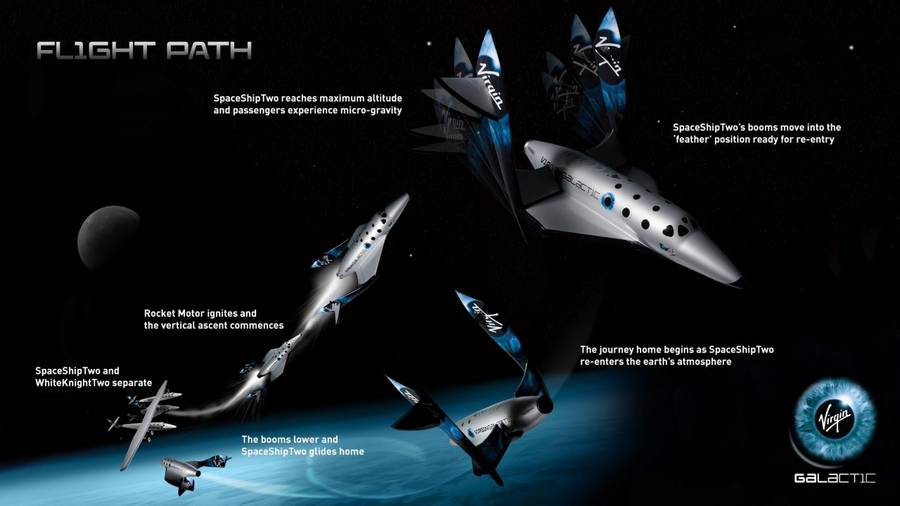

The event was 17 years in the making. In 2004, Tier One, a Burt Rutan project with funding from Microsoft’s Paul Allen, won the Ansari X Prize. Tier One’s White Knight One and SpaceShipOne, had the same mission profile as Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo and White Knight Two. The difference between the two is that the latter combination has passengers. And as we saw, Richard Branson became the company’s first such passenger/astronaut to space.

In our article, reporting on Richard Branson’s and Virgin Galactic’s space achievements, we wrote:

“Dave Mackay and Michael Masucci took over and fired Unity’s rocket engine, powering it to an altitude of 282,000ft/53.4 miles. As promised, Richard Branson and the rest of the passengers reached past the 50-mile boundary, defining ‘official’ space.”

However, one of our readers pointed out that there is a discrepancy here. Space, as a goal for Branson’s Virgin Galactic, was anything beyond 50 statute miles – which they reached. However, some would argue that this is not space – although who you ask about it, is quite important. According to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the internationally-recognized record-keeping body for aeronautics, space begins at the Kármán line. This is at 100 kilometres, or 62.14 miles.

Specifically, FAI defines ‘Aeronautics’ as aerial activity, including all air sports, within 100 km of Earth’s surface. And they define ‘Astronautics’ as activity more than 100 km above Earth’s surface.

Branson, Space and the Kármán Line

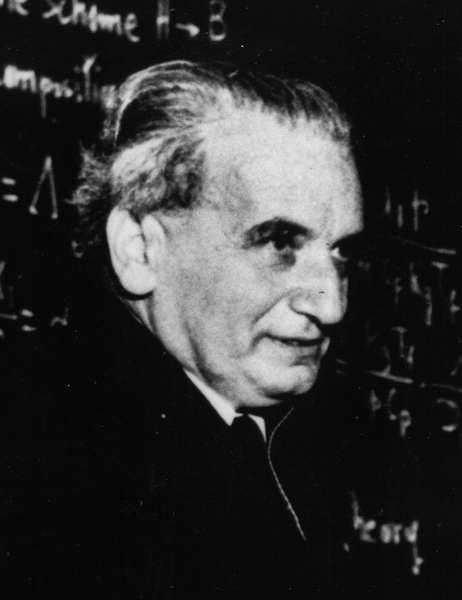

It is this distinction between Aeronautics and Astronautics that Kármán argued, to define the ‘edge’ of space. So in his effort to reach space, Richard Branson was 8.74 miles or 14km (or 46.147 feet) short. At least that’s according to FAI. But does everyone agree with them? And who is this Kármán fellow?

Theodore von Kármán was a Hungarian-American engineer, active in aeronautics and astronautics in the 1950s. “The Kármán line” has his name because he was the first in trying to define a practical ‘edge’ of space. This isn’t an easy feat, because technically, no such “edge” exists; the transition is extremely gradual. A physicist might define space as the upper end of the Exosphere – at 10,000 km. But with that definition, the International Space Station isn’t in space!

Richard Branson and Virgin Galactic use the U.S. Armed Forces definition of space, which is indeed 50 miles. But interestingly, this is NASA’s current definition as well. NASA actually used the 100 km Kármán line to define space since the 1960s – until 2005. They then switched to the 50-mile definition, for purely practical reasons.

Some astronauts in NASA projects were civilians, while others were military. In the X-15 program in particular, there were cases where people got astronaut wings if they were military, but not if they were civilians. And that hardly seemed fair, so in 2005 NASA changed its stance and retroactively gave astronaut status to several pilots. And the flight Branson had, went higher in space than some of these pilots…

It’s Complicated

Honestly, people much cleverer than the author have been arguing this topic for very long, without a definitive answer. So we won’t solve this here. But there are a few points worth mentioning. Firstly, there is no legal definition of space. So nobody can accuse Branson or Virgin Galactic of misleading anyone. Secondly and perhaps more importantly, von Kármán himself likely wouldn’t object that Branson reached space!

What von Kármán was essentially trying to argue, is that space is where you can’t operate a vehicle aerodynamically. Obviously, this depends heavily on the speed of the vehicle. Kármán himself used 300,000 feet (91km, 56.5mi) as an altitude where aerodynamics wouldn’t help control a vehicle. And it so happens that SpaceShipTwo (VSS Unity) reconfigured itself for re-entry after shutting off its rocket engine. This was well before reaching the apogee of 282,000ft/53.4 miles.

In other words, the vehicle Branson was in, was demonstrably at an altitude where aerodynamics were irrelevant. If this wasn’t the case, when the vehicle rotated its elevators (or are they stabilators?) 90 degrees, there should have been an aerodynamic effect. There wasn’t. This was the moment Branson and his fellow passengers unstrapped and started enjoying zero gravity – in space!

Branson, Virgin Galactic and Others In Space

Also, we now know that it is possible for a satellite to have an elliptical orbit with a perigee (lowest point) of 80-90km. For a few orbits, anyway. For this reason, some argue that FAI’s space limit needs to get down to 80km – coincidentally, a hair under 50 statute miles.

That said, there are other space attempts that choose to follow the FAI definition. Unlike Branson, Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin’s New Glenn capsule aim to reach 62 miles/100km in its foray into space. And closer to Virgin Galactic, their predecessors won the Ansari X Prize by reaching the coveted 100 km.

How much does any of this really matter? Very little. Bragging rights for the highest flight-aside, in a few more days both Branson and Bezos will have felt the weightlessness of space, while gazing at the earth below them. It is highly unlikely that their passengers will notice the difference. Even if it is ~46.000 feet – out of 282.000!

1 comment

Thomas Kagwa

How accurate is this statement, “So in his effort to reach space, Richard Branson was 8.74 miles or 14km (or 46.147 feet) short.”?