Airbus is unhappy with what it sees as a relatively lower focus among jet engine makers in the US (GE, P&W) on hydrogen propulsion.

In 2020, Airbus announced its intention to start development of a new airliner that would run on hydrogen. The European manufacturer showed renderings of several possible versions of such aircraft then – and more since.

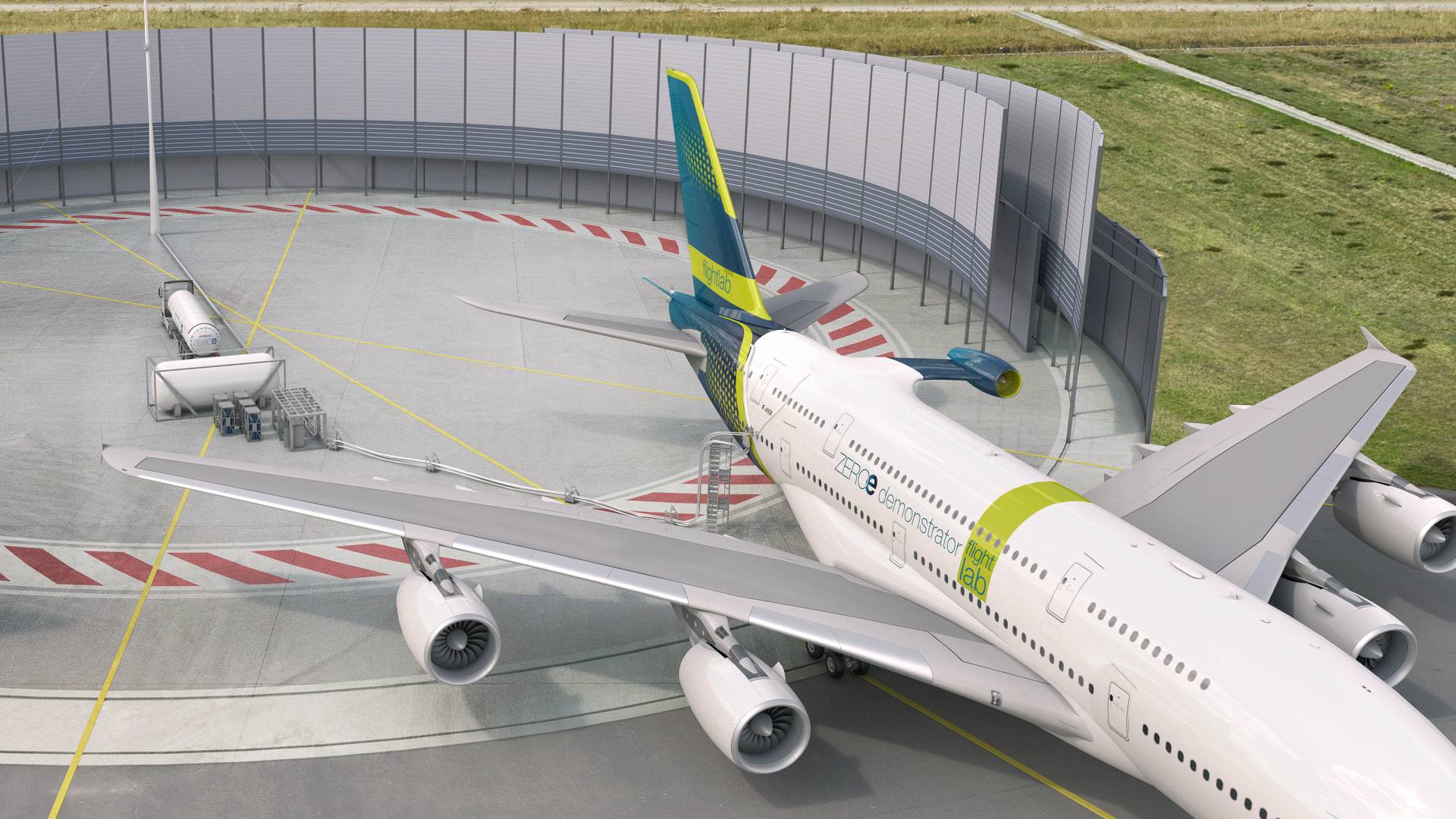

This is the Airbus ZEROe program, and the manufacturer initially planned for the first such aircraft to enter service by the mid-2030s. And from the start, Airbus tried to engage various engine makers, to join research efforts into the complications of a hydrogen powertrain.

Aircraft could use hydrogen either to power relatively conventional gas turbines, or to generate electricity in fuel cells, to then power electric motors. The aircraft manufacturer’s different ZEROe concept versions featured both methods of hydrogen propulsion.

However, according to Aviation Week, not all engine makers have engaged in hydrogen research in the same way. Airbus has recently been pointing out that European engine makers have taken the lead on hydrogen propulsion.

Airbus would like to see aerospace giants like General Electric and Pratt & Whitney do a lot more in this field. Their expertise will add substantial resources to the project, which should now be accelerating as we’re coming up to a decade from Airbus’ original target date for service entry.

Airbus Wants a Variety of Hydrogen Engine Makers…

Going further, Airbus doesn’t want to see a situation where it doesn’t have a choice between engine makers when hydrogen becomes a viable option for aircraft propulsion. There are also geopolitical implications, according to Airbus, with China’s aviation industry also set to work on hydrogen propulsion in the future.

Interestingly, the first large jet engine that Airbus plans to test hydrogen combustion on is a GE Passport. The engine, which normally powers business jets, will be mounted on a modified Airbus A380. But the Passport is a modern engine design, sharing some elements of the larger CFM LEAP.

However, even though the Passport is a GE engine, it seems that Safran is taking the lead in the Airbus test project, through its CFM partnership with GE. It is likely that Airbus’ frustration isn’t aimed at the two U.S. engine makers, but at a lack of hydrogen propulsion funding from institutions like NASA and the FAA.

By contrast, NASA, Boeing, Pratt & Whitney and GE have been researching other aspects of future propulsion, including usage of Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) and more efficient jet engine cores.

Aside from engine makers, Airbus has been working with airports, to study what kind of infrastructure will be necessary for hydrogen use. This includes airports in the United States and Canada, like Atlanta, Houston, Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver.

Hydrogen infrastructure at airports and its logistics more broadly, will be a significant challenge in making the new technology viable for aviation. And if Airbus is to achieve its mid-2030s deadline, the certification timeline of such a technological leap is also becoming a factor.

1 comment

Adyansh Sarangi

Good info