The sixth part in a series on the history of how humanity conquered the sound barrier. Written by Dale J Ferrier

Hopes Robbed

As the Second World War progressed, the Germans were not the only ones working on radical aeronautical projects. By the middle of the war, the British government was already turning some of its time towards considering the shape of aviation after the war. In 1942, the Air Ministry drafted Specification E24/43 which outlined the requirement for an experimental turbojet aircraft capable of reaching 1,000mph at 36,000ft within 90 seconds of takeoff.

This was a daunting prospect for a time when jet technology was very much in its infancy. One would expect such a substantial leap in aviation technology to be handled by one of Britain’s major aircraft manufacturers such as Vickers, Avro, or indeed Supermarine whose Spitfire was designed in the name of speed. But it would be a little-known entity that took on the mantle for such a revolutionary and record-breaking design; Miles Aircraft.

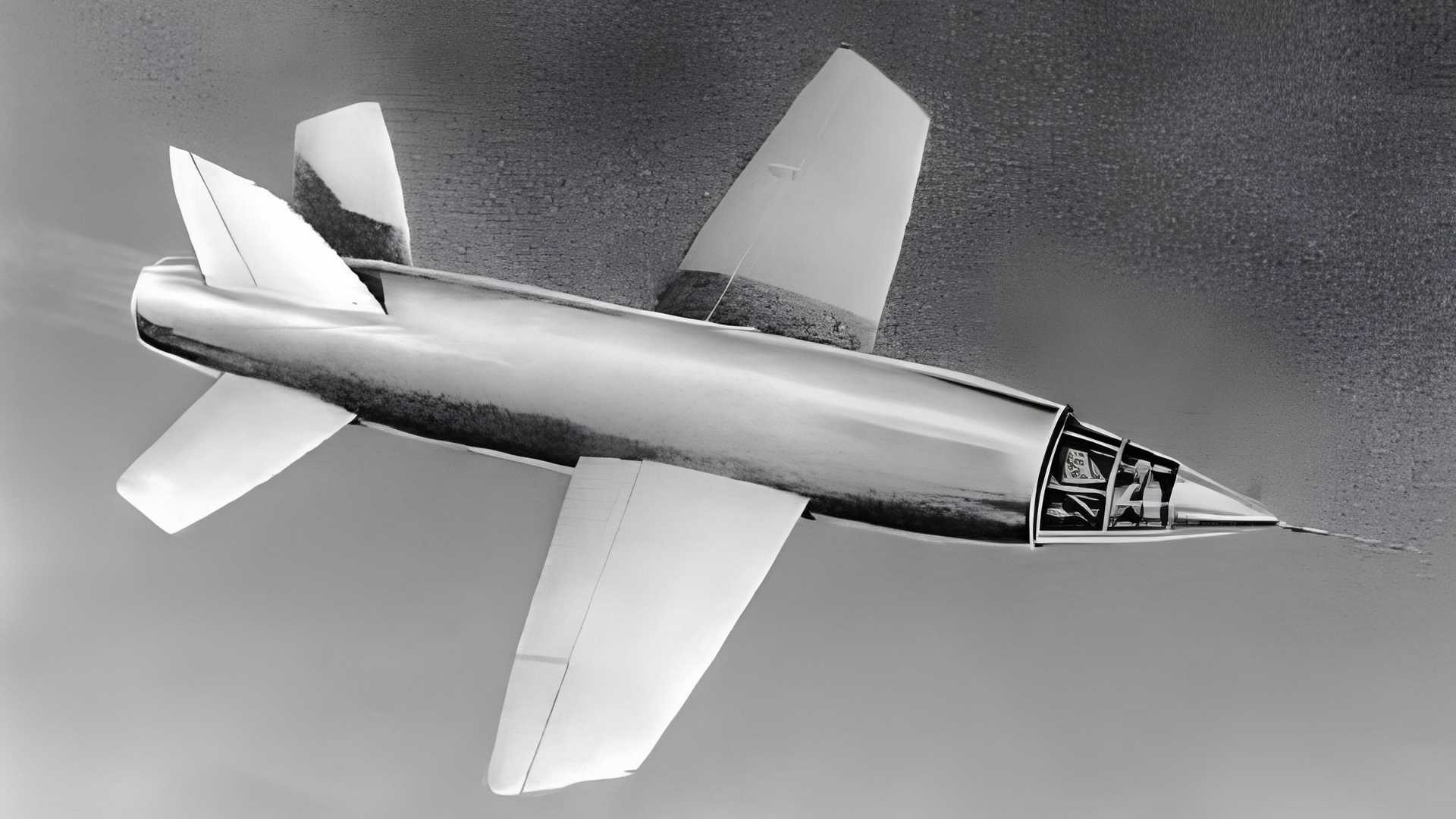

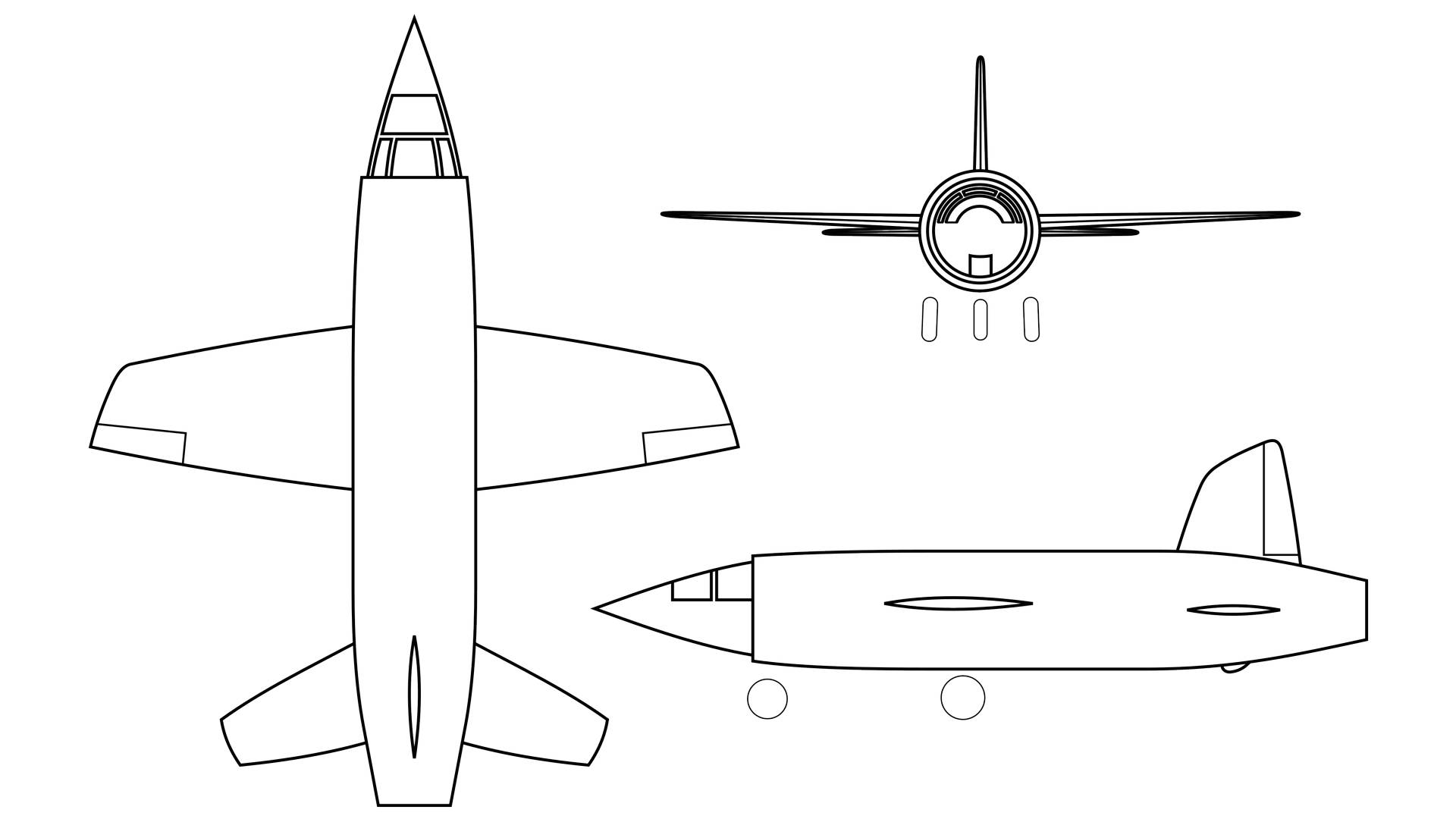

The team at Miles set about building their Supersonic jet naming it the M52. Unable to follow much of the conventional wisdom on aircraft design, they based theirs on a bullet which they knew to fly at such speeds. But unlike a bullet, the M52 would have wings. Normal wings used even on the fastest aircraft at the time just wouldn’t cut it for achieving the tremendous speed the Air Ministry demanded.

Thankfully for Miles, a great deal of research had gone into the behaviour of airfoils in supersonic flows and so they knew the wing they needed would be all metallic and razor thin. Their wing design was so thin – and razor-like – that Dennis Bancroft who oversaw the M52 project recalled that engineers often cut themselves on the leading edge.

Razor thin wings did however present another problem. In many aircraft, the fuel is stored within the wings, but there was no room since the M52’s wings were so thin. Therefore all the fuel the jet needed had to be stored within the fuselage. But, the engine required to propel the aircraft to the specified 1,000mph would consume a great deal of the space available.

To get around this, the Miles engineers developed a tubular fuel tank that would wrap around the engine, allowing for an unobstructed intake. This however meant an increase in the diameter of the fuselage. To help counter the additional drag this would cause, the cockpit was relocated to the very front and housed in the intake shock cone. This 2 in 1 design feature meant that the cockpit was very cramped and any pilot flying the M52 would be almost laying down.

The wings were however the least of Mile’s worries. For quite some time, one of the biggest hurdles to achieving supersonic flight was the loss of control whilst transitioning through the transonic range. When an aircraft reaches these speeds and more importantly its Critical Mach, the Centre of Lift shifts abruptly rearwards resulting in a pitch-down effect, or Mach Tuck as it is known. Normally hinged elevators did not work to counter Mach Tuck as the shockwave that forms on the tailplane would ‘mask’ the elevators rendering them useless. To get around this, Miles developed the all-moving tailplane so that although shockwaves would still form around it, pitch control is maintained and therefore the pilot could counter any effects of Mach Tuck and remain in control of the aircraft.

To exceed Mach 1, Miles had to do more than rethink the aerodynamics of their design – they needed a powerplant to match. The engine that would drive the M52 to its incredible speed would be the Whittle W2/700 developed by Power Jets Ltd. This engine, however, like the rest of its host aircraft, would not be conventional. The standard W2/700 turbojet just wasn’t powerful enough, so it was somewhat modified. The Power Jets team developed an aft turbofan to drive more air out of the exhaust. The exhaust of the engine core combined with the additional bypass air would then go through an afterburner drastically ramping up the power available – enough to penetrate through the powerful wall of drag at the Speed of Sound.

The Miles M52 must have felt worlds apart from Frank Whittle’s jet demonstrator less than a decade earlier. This was an aircraft that looked straight out of the world of science fiction and gave the greatest hope of Britain achieving the goal of supersonic flight. All was set for its first flight in the summer of 1946. Miles’s all-moving tailplane, crucial to getting through the transonic range, had been proven on a modified spitfire. And the country’s best test pilot, Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown was scheduled to take the M52 through her paces. Aviation glory was in clear sight. But it wasn’t to be, because in February of that same year, the project was suddenly and inexplicably cancelled.

The Miles engineers were left dumbfounded. They were on the cusp of making history. The first M52 was almost finished, and the second was not far behind. 2 years of hard work by Miles and Power Jets, not to mention the sum of £100,000 of taxpayer’s money (a not insignificant amount in 1946), had been already spent. The Lead Engineer at Miles, Don Brown, was damning suggesting that the cancellation of the project had thrown away Britain’s chance of being the first to achieve supersonic flight. Test Pilot Eric Brown was said to be ‘hopping mad’.

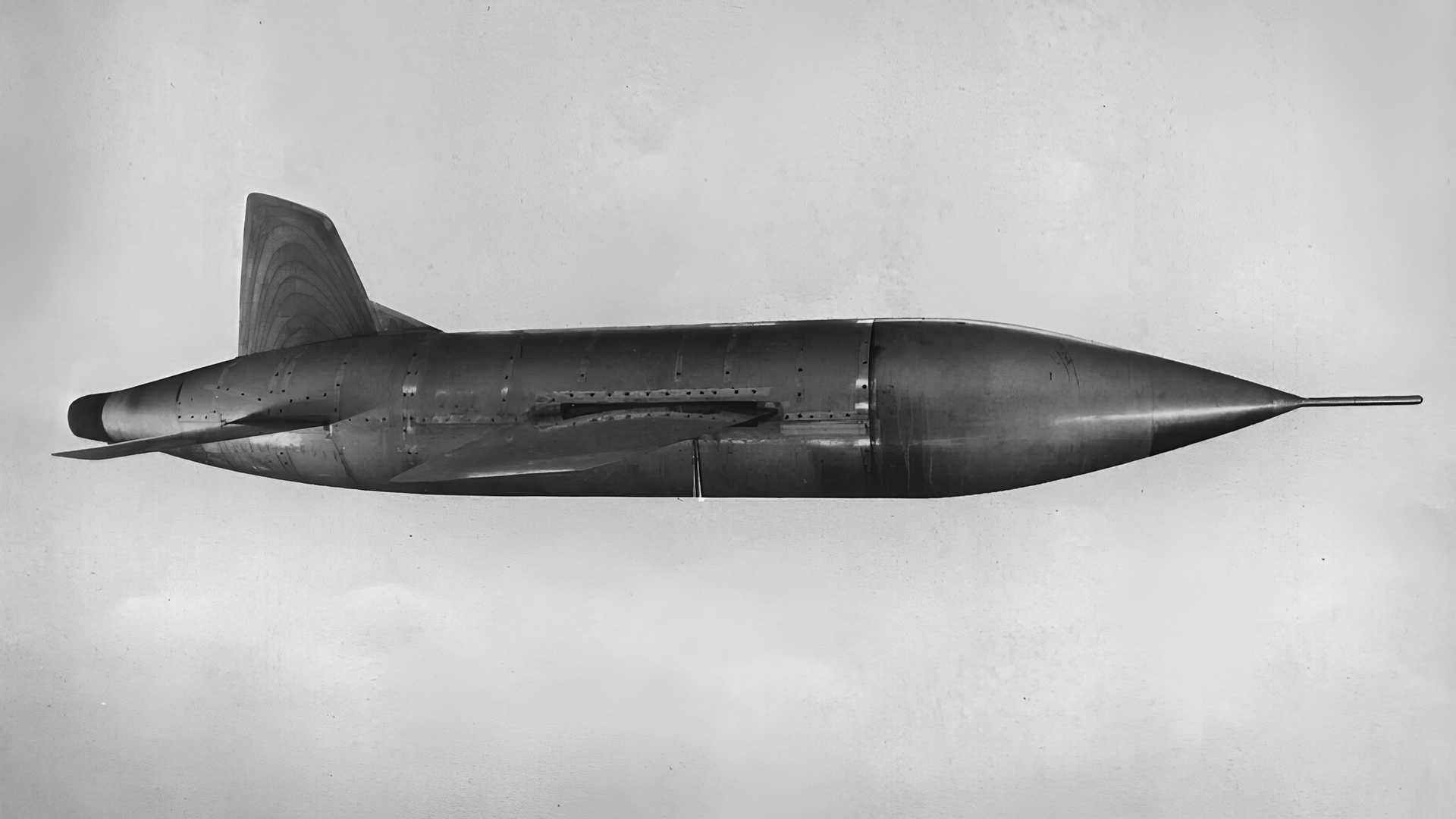

The whole project was promptly packed up and taken to the Royal Aircraft Establishment where it was taken over by Vickers and became the RAE-Vickers Transonic Research Rocket. “No danger to test pilots and economy in purpose” was the headline and led to the rehashing of the Miles project in the guise of a 3/10 scale model. The M52, which had promised so much, would now be relegated to becoming a scaled-down unmanned research model.

The cancellation of the M52 project was a major blow to British aeronautical efforts and soon suspicions arose as to the reasoning. Sir Ben Lockspeiser, Director of Scientific Research cited the dangers of flying near the Speed of Sound as to why the project was scrapped. But, with post-war austerity, it has been suggested that the real reason was the Treasury’s axe.

Not only was there anger at the government’s last-minute cancellation but also the feeling that the project was essentially given away to the Americans who were also developing supersonic designs. Back in 1944, to the irritation of Miles, Whitehall officials insisted on American dignitaries – including representatives of Bell – being allowed access to the M52 project. Supposedly Bell was already working on their very own design by this point and were experiencing issues around controllability at the transonic range, recalled Don Brown who was undoubtedly greatly involved in facilitating their American guests.

Rod Kirkby from Hawker-Siddeley suggests that Bell’s discussions with Miles led to their team increasing the power of the tailplane trimmer, which didn’t resolve the control issues. It was only when Bell developed an electric trimmer that moved the entire tailplane to alter its incidence was the issue resolved. Just how much Miles’s design influenced the X-1 is mired in rumour and speculation.

But regardless of whether it was developed independently by Bell, or adopted from Miles, the moving tailplane would be crucial to achieving supersonic flight. Yeager’s flight in the X-1 spurred the Daily Express newspaper to campaign for the restart of the Miles project, but without success.

The smaller rocket-powered model of the M52 used for missile research showed that Miles’s design may have exceeded their somewhat pessimistic performance estimates. The first model exploded when the rocket motor was ignited, but in the second test in October 1948, the little model shot off to supposedly reach Mach 1.5. According to other sources, it may have reached only Mach 1.38.

During this test, the model was supposed to plunge itself into the sea once the rocket fuel had been expended. But, instead, it carried onwards towards the west over the Atlantic and disappeared – perhaps to find its American cousin. The final nail in the coffin for the M52 came when these tests were also cancelled due to their “high cost for little return”.

In a different history, the first sonic booms may have been heard over the damp shores of Blighty, but it wasn’t to be. That achievement would occur thousands of miles westwards, in the skies of California.

End of Part VI