The Basler BT-67 turboprop conversion of the DC-3 continues to operate in many demanding environments today. But why is there a need for it? What does this aircraft do, that more modern airliners can’t?

The DC-3/C-47 ‘Skytrain’ or ‘Dakota’ (depending where you are) needs no introduction. Before the 747 or the Concorde became iconic commercial aircraft legends, the DC-3 was carrying people and cargo all over the world. It was the default airliner and cargo plane. There were bigger and faster planes that could also do the job, of course. But the Douglas plane was ubiquitous, and reliable. And with its much-refreshed new persona, the Basler BT-67 is still carrying its torch.

But why? As aviation geeks, we all like to see iconic aircraft like this. DC-3s always steal the limelight in any airshows. But conversions like the Basler BT-67 are not for the airshow crowd. So, who are they for? And more to the point, why do they choose this old design over other, newer aircraft? The answer is simple: they choose it, because it does a good job!

Current users of the Basler BT-67 are a clue to its success. None of its operators are what you might call ‘large scale’ – although within their individual fields, they may well be. What they operators of the aircraft have in common, is that they all want to go somewhere difficult to get to. A combination of distance, terrain and runways (or lack thereof) make for conditions that the Basler BT-67 excels in.

The Basler BT-67’s Purpose

It is unquestionably a niche aircraft. It goes to Antarctica, to the Canadian North, and to dusty or muddy terrain in Africa and Central America. Its users include researchers, military forces, firefighters and, of course, cargo companies. Researchers need it because of its ability to go to some remote places, but not always. Sometimes the Basler BT-67 is, in itself, the research instrument.

There are of course other aircraft that can go to snowy or muddy places. The C-130 comes to mind or, at the smaller end, the Twin Otter. But for some tasks, alternatives are often too big, too small or too expensive. The DC-3 was big enough, fast enough and could land there. The only problem was that it was too old. And could use a bit more power, too. So, that’s how the Basler BT-67 came to be. In the words of Warren Basler, the thinking behind it was as follows:

“The DC-3 was a beautiful, stable, and virtually indestructible airframe going to waste. We realized that by turbinizing and modernizing the airplane it would go on for many years.

“For years the aviation industry had been searching for a replacement for this rugged and reliable aircraft… at Basler Turbo Conversions we’re building it.”

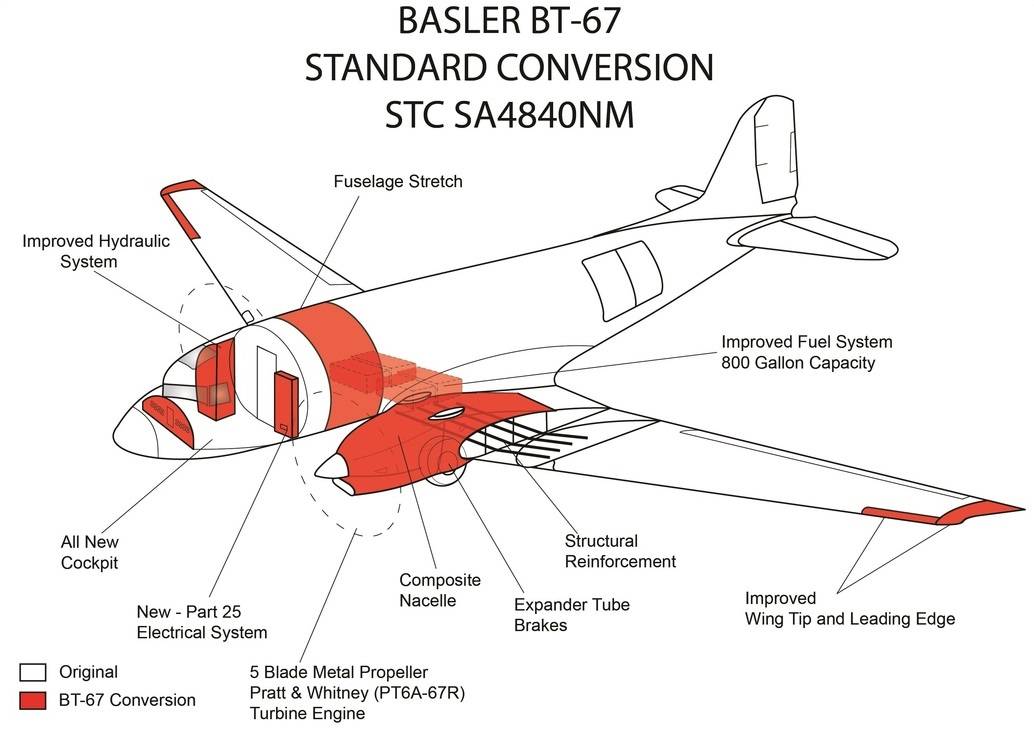

Basler started conversions to the BT-67 standard in 1990. Warren Basler passed away in 1997. By then the company had changed hands, and pressed on. The operation to convert a DC-3 to a BT-67 is quite extensive. In essence, the entire aircraft is dismantled and rebuilt. It also undergoes quite a few changes, big and small, that go well beyond those engines.

Some New Weight And Balance Calculations

The fuselage of Basler’s BT-67 gains another 95cm (37”) in length. Interestingly, all of this extra length goes in front of the wing. That has a lot to do with those engines, and their weight. DC-3s and C-47s had Pratt & Whitney engines, either the R-1820 Cyclone or the R-1830 Twin Wasp. Both of them are nice, big, radial piston engines, burning aviation gasoline.

The Basler BT-67 has the Pratt & Whitney Canada PT-6A. This is one of the most ubiquitous turboprop engines in use today, with both military and civilian applications. The version Basler selected is PT6A-67R, developing 1,424 shp. However, each PT-6A weighs 233kg (515lbs). That’s not even half the weight of the radials! The lightest of those is the 1000hp R-1820, at 537kg (1,184lbs). The 1,200hp R-1830 weighs 567kg (1,250lbs).

So the turboprops make significantly more power and weigh half as much as the radials. This weight difference required stretching the Basler BT-67’s fuselage, forward of the engines. That’s despite the fact that the engines necessarily sit forward of where the radials were. The weight reduction also has interesting implications, with regard to the plane’s useful load. But Basler made that even more impressive, by strengthening the airframe, to increase its gross weight.

The effects of the combination are staggering. The Basler BT-67 is 529kg (1,166lbs) lighter than a typical DC-3. That’s despite the extra fuselage length, a slightly longer wing and strengthening to increase gross weight! MTOW is 1,610kg (3,549lbs) higher for the Basler. This translates to around 43% more useful load by weight, plus 35% more volume, thanks to the longer fuselage.

Basler’s Other Updates in the BT-67

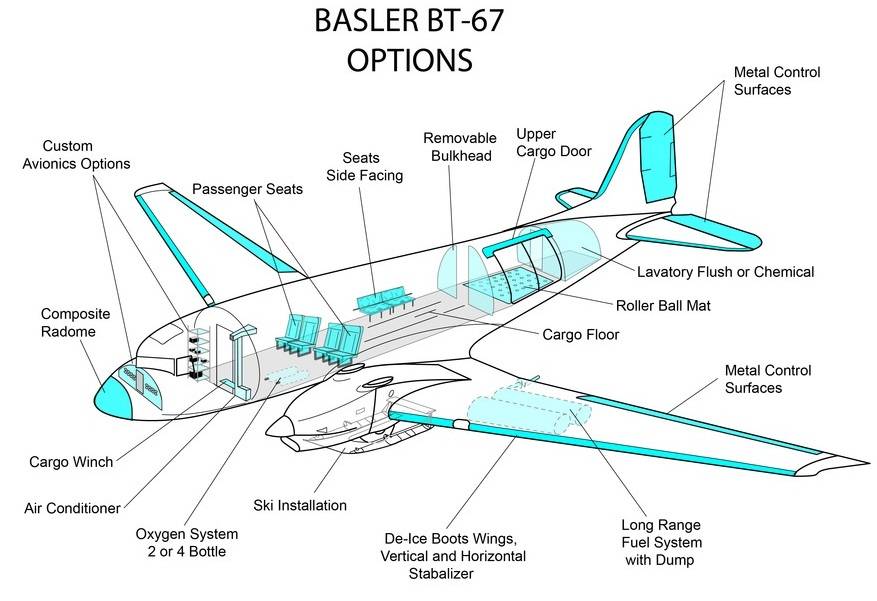

But the purpose of this plane is to get to difficult places. Aerodynamic improvements give the Basler BT-67 lower approach and stall speeds, which helps. It’s also faster in cruise, but at the expense of fuel consumption. At ‘DC-3’ speeds, it burns about the same amount of fuel. But now the engines drink Jet-A, not Avgas. Buyers can stick to the existing fuel capacity… or they can double it. Some do this, to transfer fuel to remote locations.

Since Basler has to disassemble the entire plane to build the BT-67, they give it some brand-new toys. Among them is a new cockpit, a new fuel system and electrics. If customers pick extra fuel tanks, they also get fuel dumping. But customers can also choose things like de-ice boots on the wing and the vertical and horizontal stabilizers. Since many of the planes spend a lot of time around ice, this comes handy for many of them.

The original DC-3 and C-47 was NOT a niche aircraft, it was a utility workhorse. It was actually so good that it nearly killed commercial aviation development. Airlines knew that newer planes would be more efficient. But they could buy surplus C-47s at almost scrap value. Eventually aviation moved along, but the DC-3 airframes were rugged and overbuilt.

The Basler BT-67 certainly is a niche aircraft but it’s still a utility workhorse. And yes, those radial engines were prettier. But thanks to these conversions/rebuilds, the shape of that iconic aircraft will stay with us for a bit longer. However those of us living in cities, will need to travel a bit, to see them…

All photos are from Basler Turbo Conversions

2 comments

Andy RENDELL

A geophysics survey Basler was scanning. Cornwall this month at low altitudes,typically 250- 350ft or lower, and a steady 115 kts. It was on clear,still,fairly cool days (7-8C,) giving stable conditions. It was clearly an approved safety approved flight plan over mainly sparsely populated areas but I windered how much room for error or contingency there was. Presumably not loaded other than for fuel and bot especially heavy telemtery and data recording/ processing kit. Any comments?

Jim Roberts

I’d love to fly the Basler BT-67 to “complete the circle”…my first ride was a DC-3. Of course I’ve not been pushing throttles for decades but you never forget how to ride a bike either. 🙂