This is the first of two articles, covering the origins and evolution of commercial aviation in China, from the beginning of the 20th century until today. Written by Dale Ferrier, creator of The China Crane.

A Brief History of Chinese Commercial Aviation: 1900 – 1949

20th Century China is a story of tremendous upheaval and chaos – the collapse of the Qing, warlords, invasion, civil war, famine, revolution, and reforms have meant that from the time when the century began to when it came to a close, for China, the changes were so epic that it might have as well been a thousand years. Throughout this however, China’s airlines were born and took on new roles as each tumultuous era passed from one to the next. In this first part, we shall see how Chinese commercial aviation was born, and how its first carriers arose – and fell.

Early Pioneers

The attraction of flight has been with the Chinese since ancient times with the construction of simple balloons and kites, flown and enjoyed for centuries. The concept of human flight however seems to have entered the fray when Wan Hu strapped himself to a rocket-laden throne during the 16th Century. Disappointed in his belief that the entirety of the Earth was known, he dreamt of venturing to the stars. In an eruption of smoke and flame, Wan disappeared and was not seen again, creating the legend of China’s first astronaut. Whatever the fate of Wan, it wasn’t until the 20th Century that we would see the more convincing beginning of Chinese flight.

The first time a human officially flew aloft over Chinese soil was in 1909 with a Sommer biplane at the hands of French aviator Vallon, who amazed onlookers in Shanghai – that is until he lost control and crashed into a racecourse, killing himself in the process, horrifying the same people who watched in awe only moments earlier. However, early Chinese involvement in aircraft can be illustrated by the work of at least a couple of daring individuals.

Feng Ru, born in 1883, moved to the United States at 12 years of age without an education. He is credited as being the first Chinese man to fly after constructing and flying an aircraft of his design in September 1909 in Oakland, California, according to the Oakland Enquirer newspaper at the time. Unfortunately, anti-Asian dispositions placed doubt on Ru’s achievement with The Aeronautics magazine declaring that his machine flew ‘three-quarters of a mile in a circle on its first trial, but this is extremely doubtful for many obvious reasons.’1

27 Years earlier the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed prohibiting the migration of Chinese labourers to the US for 10 years. It too meant that Ru, like many other immigrants from China, were denied US citizenship and led highly segregated lives. So when Dr Sun Yat-sen heard of Ru’s flight, he requested his return to China to help in his revolution against the Qing. Feng Ru was very abiding and arrived back in his native country in March 1911, bringing with him a Curtiss biplane. He though was killed in August the following year when he crashed whilst piloting a demonstration flight in front of over 1000 spectators at Yantang airfield. Dr Sun requested that he be buried at the mausoleum of the 72 Huanghuagang Martyrs with ‘Pioneer of Chinese Aviation’ inscribed onto his tomb. Ru’s untimely death meant that his hand in China’s aviation development was quite limited – unlike that of another first.

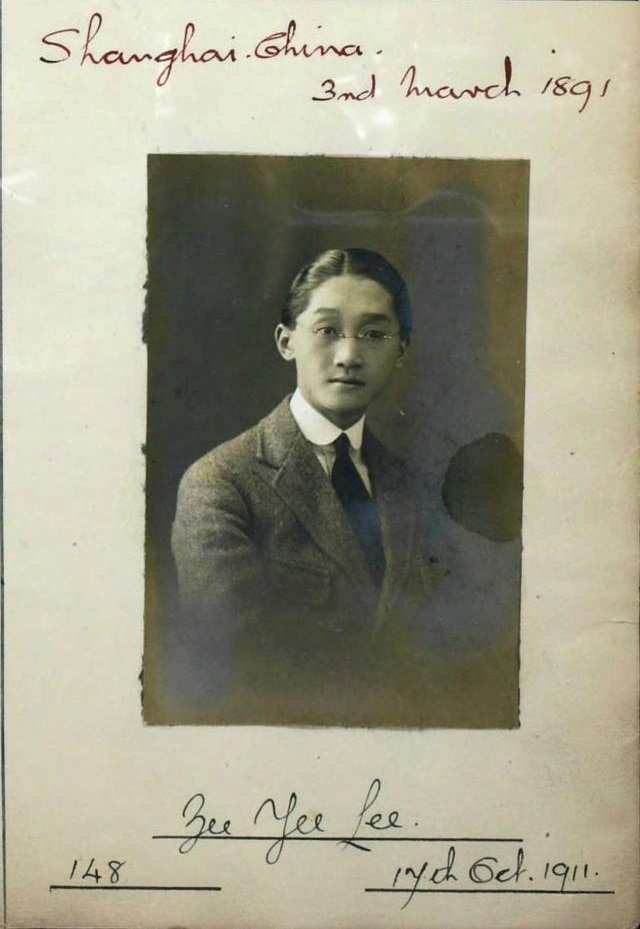

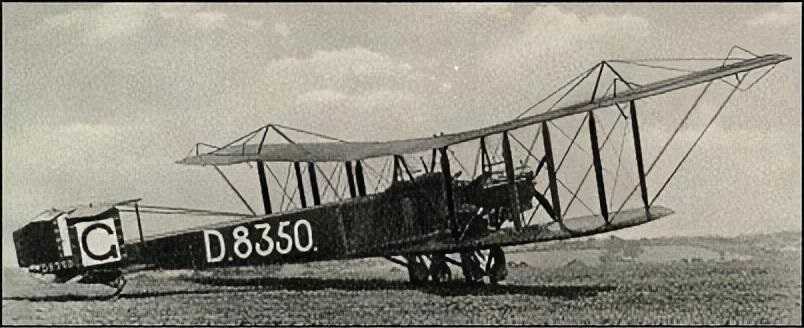

Zee Yee Lee was born in Shanghai, 1891 and went on to study at an industrial school in London, graduating in 1909. A year later he joined the Bristol Aeroplane Company at the request of his government to study aircraft design. The company had gained a reputation for their aircraft and its instruction on flying them. On the 17th of October 1911, Lee obtained his Royal Aero Club certificate No. 148 under the instruction of Bristol’s Howard Pixton in a Boxkite aircraft of the same company on Salisbury Plain to much acclaim in early aviation magazines. Lee is often considered the first because he remained a subject of China, as opposed to the Ru as mentioned earlier who left for the US at a young age.

Lee, with two others, established China’s first airline route in March 1914 between Beijing and Baoding. This was however short-lived as rivalries between China’s first president Yuan Shi-kai and regional warlords meant that it wasn’t until the 7th of May 1920 that a regular passenger and mail service was established between Bejing and Tianjin. In fact, relative stability after Yuan’s death in 1916 led to a renewed interest in building a civil aviation industry due to the lucrative promises it made in connecting its commercial hubs, and the simple prestige provided by having such a new and exciting industry. Therefore interested European, particularly British, manufacturers were keen on meeting these needs. With the First World War just ended, the allied powers had an enormous surplus of aircraft which they were all too happy to sell off to the Chinese. The British emerged on top with officials from Beijing negotiating with Vickers and Handley-Page, with the latter securing a deal in February 1919 for six large 0/400s powered by two 350hp Rolls-Royce engines for £10,540 each. Vickers would not miss out though, going on to secure a larger deal of 95 aircraft resulting from rebellious factions seeking to compete and cash in on the new promising venture.

These aircraft went on to serve the early test flights of the 80-mile Beijing – Tianjin service. This however went the way of its predecessor and was dissolved following the breakout of hostilities in the region with General Ting Shih-yuan, who headed the operation on behalf of the government, commandeering the aircraft for military use. The flame had seemingly gone out on these early Chinese efforts.

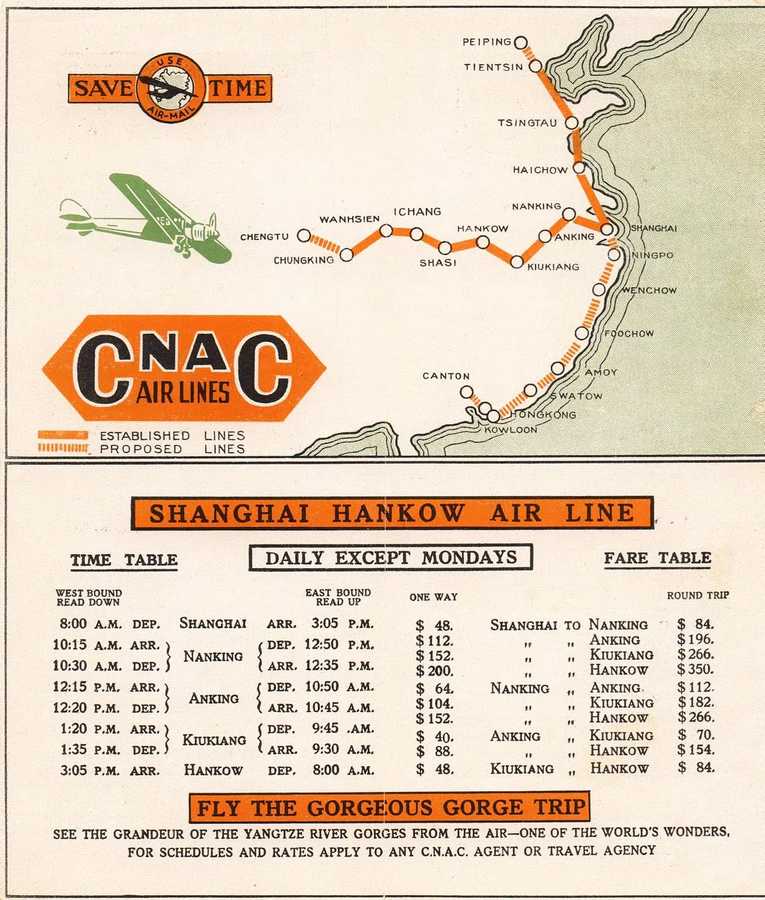

There were attempts made, but it wouldn’t be until 1929 that the promise of regularly scheduled services would reemerge. The American company Aviation Exploration started the first true airline service under a franchise issued under the Ministry of Communications. Becoming China Airways in 1930, they operated a network of passenger and mail services on behalf of the state-owned China National Aviation Corporation. That same year China Airways, CNAC, and the also state-owned Shanghai-Chengtu Line were amalgamated into CNAC. Although sharing the same name as before, CNAC was an entirely new enterprise with joint Sino-American management, but with the majority ownership being with the Chinese state. Centred in Shanghai with a fleet consisting of five Stinsons from the Shanghai-Chengtu Line and the five Loenings of China Airways, along with a further six, the new airline operated three main routes for which it had exclusive rights; North to Beijing, South to Guangzhou, and west to Chongqing deep in the interior which was beyond central government control. With several stops along each route and proving considerably more successful than the earlier attempts, CNAC accounted for 15,000 passengers over its 5,000km network by 1937. That was however not without difficulty. Subject to political turmoil and financial issues in the early 1930s, CNAC would almost fall several times if it weren’t for the determination of those who worked for them. In 1933, Pan American Airways bought the American stocks in CNAC to complement its planned transpacific services and operated two Sikorsky S-38 amphibious aircraft on the Guangzhou – Shanghai service with CNAC liveries, with services to Manila starting soon after.

They too weren’t the only ones. The provincial governments of Guanxi and Guangdong formed their own carrier by the name of the Southwest Aviation Corporation in 1932. And Eurasia Aviation commenced services between Shanghai, Beijing, and Manchuria using single-engine Junker W-33s. This particular service was a joint agreement made between the Chinese government and Deutsche-Lufthansa with a two-thirds/one-third ownership respectively. Carrying passengers and mail to Manchuria, the agreement entailed that those wishing to continue could travel onwards to Moscow, and then finally to Berlin with Lufthansa themselves. This changed after a single flight, resulting from the Kremlin’s paranoia over foreign aircraft, to passengers taking a train from the Sino-Soviet border to Irkutsk, then Soviet carriers all the way to Berlin. Eurasia’s Berlin service was however ill-fated, and a lack of demand meant that its initial thrice-weekly service became twice-weekly. When one of its aircraft was shot down en route to Manchuli on the border by Mongolian bandits, capturing the pilots for several weeks, Eurasia elected to stop its international services and concentrated on domestic routes where it saw better luck. Acquiring a fleet of the advanced Junkers Ju-52 tri-motor aircraft in 1935 they continued to operate in China until the Germans withdrew from there by 1941.

Demand for air travel grew tremendously in China, so much so that these new carriers struggled to meet the demand. Travelling by air in 1930s China was considerably more desirable than the alternatives. Costing an average of 10 cents a mile, flying was cheaper than overland, and generous deals on excess baggage meant that merchants looking to sell their wares in the country’s vast interior soon flocked to these ariel links. Not only did the attractive prices fill the aircraft. Despite the Nationalists under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek bringing some form of centralised government, the country was a patchwork of warlords and factions, each often having their own loyalties and with varied stability. Between the relative calm of the major cities, travelling through rural China could be a dangerous affair. Sporadic conflicts, gangs, and lawlessness generally meant that the ability to bypass all this by aeroplane proved popular.

In 1935, CNAC began to purchase newer aircraft with the delivery of three Ford Tri-motors from Pan American, and then two brand new Douglas DC-2s. The latter caused particular excitement as the Douglas was a modern airliner and a world apart from the airline’s old fleet of Stinsons and Loenings. The mid-1930s also saw improvements in weather services and radio navigation aids for which these new faster, higher flying aircraft required. But airport infrastructure was slow to improve and although some major airfields did receive paved runways, most remained as they were – a point that would come to bite them when war broke out with Japan.

Airliners go to War

On the 7th of July 1937 at the Luogou Bridge – better known as the Marco Polo Bridge – near Beijing, the absence of an Imperial Japanese soldier caused tensions with Chinese troops to boil over resulting in an exchange of fire. Other incidents had happened previously between the Chinese and the Japanese, but this incident is attributed to being the spark that triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the beginning of World War Two in Asia.

CNAC continued to operate its fleet of Douglas Dolphins, DC-2s, DC-3s, and 3 Vultee V-1As on routes away from the main theatre of fighting as the Japanese advanced. Although the airline attempted to avoid the war, and the Japanese at first honoured their non-military status, the war had a way of finding the carrier. When fighting broke out in CNACs main hub, Shanghai, a DC-2 piloted by Charles Sharp was flying in a Ministry of Finance shipment of banknotes to the city. When he landed, his aircraft was surrounded by Chinese troops who ordered him to immediately carry a consignment of bomb racks and machine guns to an airbase near Hangzhou. Sharp protested that it was a commercial airline that had no business carrying such things, and besides being American meant he had to remain neutral. The soldiers threatened to shoot if he did not comply, and so Sharp took the menacing cargo at gunpoint.2

It would not be long however before the Japanese acted against CNAC. On the morning of the 24th of August 1938, a DC-2 piloted by another American called Hugh Leslie Woods took off from Hong Kong en route the Wuzhou, the first stop on its Chongqing service. Not long after entering Chinese airspace, Woods noticed a formation of Japanese float planes maneuvring into an attack position. His DC-2 was purely civilian and so completely unarmed, and only carrying Chinese civilians. Knowing this, Woods flew around evasively into clouds to throw off the attacking Japanese, but to no avail. He decided that the best chance they had was if he performed a forced landing. Flying over rural Guangdong, there was little to offer for suitable landing areas. flanked by mountains, the valley below him contained nothing more than rice paddies crisscrossed by irrigation ditches. Putting her down here would likely result in disaster. He however luckily saw a river and performed a perfect water landing. The DC-2 was designed to float, but unfortunately, it became apparent that Woods was the only occupant who knew how to swim. He made for the shore to retrieve a boat he’d seen to rescue the passengers. The Japanese circling like vultures overhead strafed Woods and his ditched Douglas. Woods escaped injury, but his aircraft riddled with bullets began to sink. When the attacking aircraft eventually disappeared, Woods, his radio operator, and a wounded passenger whose wife and child died in his arms were the only survivors.3 The aircraft Woods flew was called Kweilin, giving the incident’s name. This became the first time in history that a civilian airliner would be brought down through military action, and was widely condemned around the world – unfortunately, this would not be the last time.

As the war progressed and the Japanese blockade starved Chinese forces of much-needed supplies, the wartime government tasked the airforce with exploring potential air routes over the Himalayas to relieve their increasingly desperate situation. In November 1941, Xia Pu, a pilot for CNAC flew from Dinjan in Burma to Kunming to chart out a way through. Flying over the high Himalayas, the route into China from Burma, and later India became affectionately named the ‘Hump’. Flying the Hump was exceedingly dangerous. High altitude, deep gorges, unpredictable weather, inaccurate maps, not to mention the menacing Imperial Japanese Airforce meant that keeping China in the fight came with great sacrifice. As the number of supply flights increased, so did the losses. One pilot with the US-led Air Transport Command Ernest Gann witnessed four crashes in one day, losing 32 people.4 Often, the morning flights would see the ridges and mountain sides glisten with the twisted wrecks of those who didn’t make it.

Bolstered by an additional 100 aircraft from the US, CNAC transported some 75,000 tons of supplies out of the total 650,000 tons total over the ‘Hump’ providing critical supplies to the Chinese forces resisting Japan. CNAC was also a vital lifeline for the besieged city of Hong Kong when Japanese forces attacked in December 1941, flying 16 sorties from Chongqing, they successfully evacuated 275 people out of the city, including the widow of Dr Sun Yat-sen, Soong Ching-ling.

In 1945, Japanese forces surrendered, ending over 8 years of brutal occupation and bitter fighting in China. The peace though was not to last. The Communists soon broke their allegiance with Chiang and triggered the Chinese Civil War which ended up being just as destructive as the war with Japan. CNAC returned to Shanghai in 1945, having relocated to India during the war, where they renewed their contract with Pan American for 5 years with the Americans owning a 20 per cent share. They too began services to San Francisco using their DC-4s acquired during their time flying over the Himalayas. The airline’s war work continued by flying freight for the government, including into the city of Shenyang in 1948 which by this point was surrounded by General Lin Biao’s Communists. CNAC carried over 3,400 tons of supplies, mostly food, into the isolated city before it finally surrendered to Lin. Thanks to CNAC’s efforts, the people of Shenyang escaped the hellish siege that had befallen Changchun to their north where up to 200,000 perished, mostly by starvation.

During these times CNAC would face competition from a new airline called Central Air Transport Corporation (CATC) formed in 1943, and CAT airlines which performed a much more direct role in the Civil War than CNAC would. The airline faced serious financial troubles brought on by an economic crisis in China as the conflict grew. But worse would be soon to come. The country around CNAC, and CATC, would be flipped on its head and with it bring an end to the long and illustrious career of China’s great airline.

This was Part 1, covering China’s aviation from 1900 to 1949. Part 2 is coming soon, covering 1950 to today. We would like to thank Dale Ferrier for his kind contribution!

Notes

1. Oakland CA Chinatown Makes Aviation History, San Francisco Chronicle, by William Wong, 18th September 2009

2. The Dragons Wings, China’s Lifeline, by William M. Leary, 1976 University of Georgia Press, p.113

3. China’s Wings: War, Intrigue, Romance, and Adventure in the Middle Kingdom During the Golden Age of Flight, Going with the Wind, by Gregory Crouch, 28th February 2012, p.165

4. Fate is the Hunter, by Ernest K. Gann, 1961, p.271

Article source: The China Crane