Few people remember the Boeing Sonic Cruiser today, but at one time it was Boeing’s most promising project in a generation!

It wasn’t that long ago. In fact it was almost exactly 20 years ago, on the 29th of March 2001 that Boeing unveiled the Sonic Cruiser. Some critics opined that if they’d presented it three days later, people would dismiss it as an April Fools. But Boeing was adamant that it wasn’t a joke. This was a time when Concorde was still criss-crossing the Atlantic, and people wanted to see its successor.

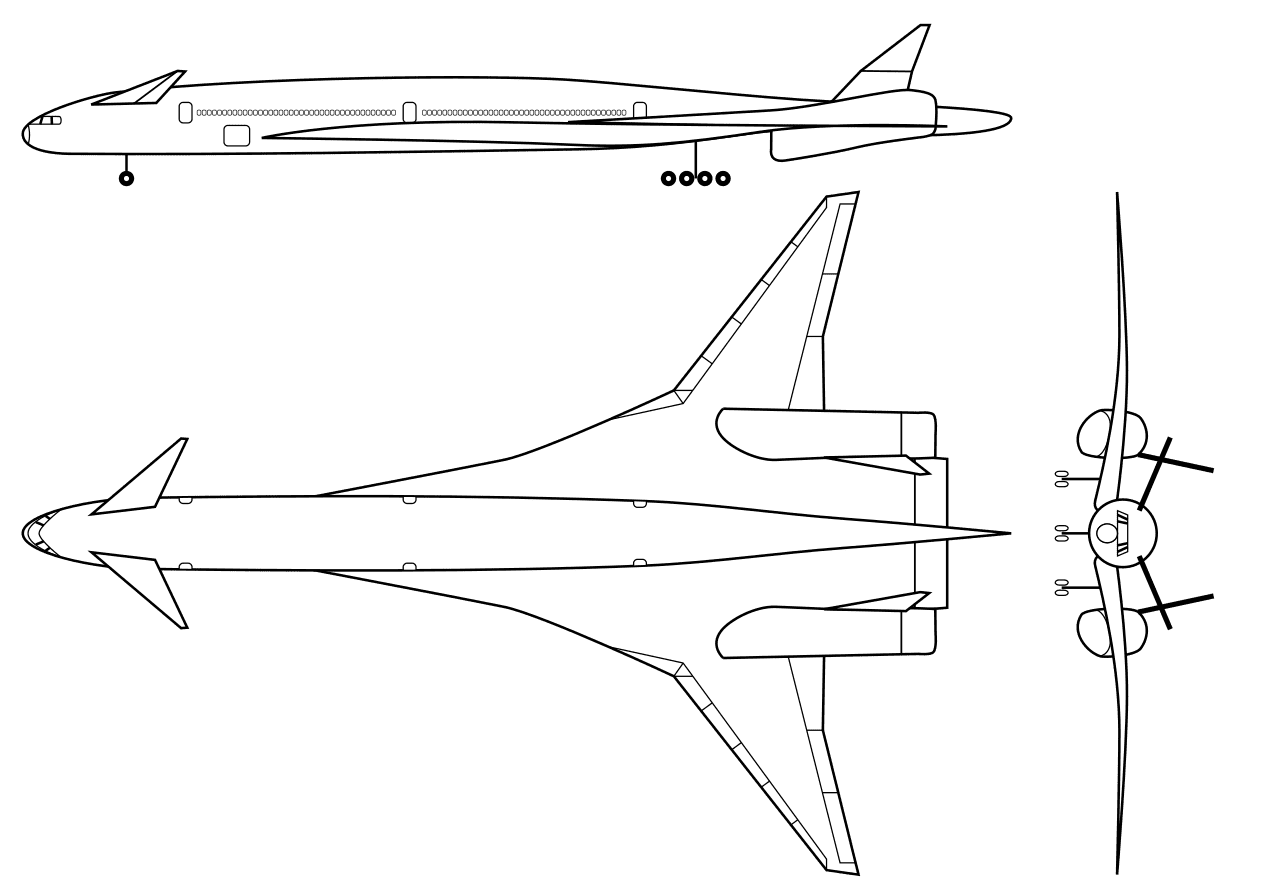

The Sonic Cruiser was a Boeing concept, for a widebody that would cruise at very high subsonic speeds. It had a delta wing, employing canards near the nose. Its wing span was similar to the 767, but it had nearly twice the wing area. The engines were not on pylons, instead they were buried in the wing. We hadn’t seen such a design since the Comet, but of course this was much different. The intakes were under the wing, while the engines themselves were towards the rear, behind an S-duct.

In all, it was a revolutionary design. Until then (and now), all airliners consist of a tubular shape for people and luggage, plus two wings and a tail. Sometimes the engines are in the rear, usually they’re not. We’ve had a couple of two-floor designs, sure. Otherwise, the average person couldn’t tell an A320 from a B767, from a distance. Within a given model, different versions consisted of making the fuselage longer or shorter. Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser would change that.

The Boeing Sonic Cruiser’s Curves

The Boeing Sonic Cruiser would follow the area rule. In simple terms, this rule varies the cross-section of the fuselage, keeping the overall cross-section as consistent as possible, front to rear. This minimizes drag, but is really only necessary at high Mach numbers or in supersonic flight. In practice, this rule means that the fuselage must change girth, becoming thinner as the wing gets larger. This is a detail that we already saw in the Aerion AS2 and other proposed supersonic designs.

But the Aerion AS2 is a business jet. Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser is a twin-aisle airliner! Manufacturing such a large fuselage with a variable cross-section, is much more difficult. Plus, different versions of it can’t just have a shorter/longer cabin. Boeing believed they could get around these challenges by using composites, which were just coming of age. This is also what Aerion and others are planning on doing with their supersonic projects.

To many, Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser was the stepping stone to a Concorde successor. Yes, it was subsonic – by a hair. But it only had two engines, and Boeing hinted at a four-engined follow-up, that would break the sound barrier. With the two-engined model capable of cruising at Mach 0.98, it seemed a plausible and intriguing thought. But honestly, this comparison really missed the point. Boeing did not design the Sonic Cruiser to compete with Concorde.

Sonic Cruiser, Boeing’s Anti-A380?

Airbus had formally started the A380 programme only a few months earlier. People still talk about the “Point-to-Point Vs Hub & Spoke” debate today, but for much of the late 90s and early 00s, it was more… fierce. The A380 didn’t just appear overnight. It had been floating around the aviation world since 1994, as the Airbus A3XX. The debate revolved around the possible size of its market. Airbus believed it was upwards of 1000 aircraft, based on the then-current growth of aviation.

Boeing didn’t agree. They could see that the Hub & Spoke model had some severe limitations. And the A380’s success depended on that model. Instead, Boeing proposed something smaller and faster. The Sonic Cruiser would allow Boeing to connect any two points in the globe, faster. People would be able to fly directly, without intermediate stops, and in a much faster aircraft! The idea was reasonable, and efficient.

However, the efficiency of Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser was the subject of much debate. Airbus claimed that they had studied a high-Mach subsonic concept, and decided it couldn’t be efficient at these speeds. The engines need to have a lower by-pass ratio, to provide sufficient thrust at higher Mach numbers. This increases specific fuel consumption. Boeing claimed a potential range of 10,000nm. Airbus and others estimated the real-world range of such a design at around 7,500nm.

Faster Than Fast Enough?

Then there’s the question of time savings. In a 3,000 mile journey, travelling in Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser would only save about an hour. That’s 5.3 hours instead of 6.3, or a gain of 20%. And while this isn’t nothing, it isn’t earth-shattering, either. Keen readers may remember an article we did on the Convair 990A. No spoilers, but… if you haven’t heard of it, the reason has a lot to do with this discussion.

To many, the eventual cancellation of Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser was the result of 9/11. It’s hard to counter this argument, given the devastating effect it had on aviation in general. But it doesn’t tell the whole story. The reality was that speed was never as important to airlines or passengers, as cost. And that’s why aircraft aren’t getting any faster. We simply have other priorities. Or perhaps jets are fast enough!

Either way, Boeing cancelled the Sonic Cruiser officially in December 2002. However, Boeing was spot-on with regard to the A380, the size of its market and the future of hub & spoke. The Sonic Cruiser didn’t die. It simply ‘morphed’ into the 7E7, which then became the 787 Dreamliner, complete with composite materials.

Still, the Boeing Sonic Cruiser is one of the big ‘what if’ points in aviation. But if the various supersonic projects we hear about come to fruition, perhaps we’ll get an answer!