It was on the 24th of June 1982 that a 747-200, British Airways flight BA009, better known as Speedbird Nine, became a glider over Jakarta.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is Captain Eric Moody again. We have a small problem, in that all four engines have failed. We are doing our damnedest to get them going again. I trust you are not in too much distress.”

This passenger announcement has gone down in history as the most understated PA, ever. But when quoted in this way, it is incomplete. Immediately afterwards, the BA009 Captain added: “Will the CSD (cabin service director) please come to the flight deck”. This was a coded message to the cabin crew, to prepare for a crash landing or a ditching.

This is the story of a flight that changed how pilots deal with volcanic ash clouds. The challenge that the crew of this flight faced made aviation authorities more aware of volcanic eruptions. Flight BA009 made aviation safer, by changing processes and developing forecasting tools to prevent flight crews from encountering such clouds.

BA009 Has Clear Weather Ahead?

This was a multi-leg flight, originating in the UK and ultimately reaching Auckland in New Zealand. Along the way, it stopped in Bombay, Kuala Lumpur, Perth and Melbourne. The incident flight was the 3rd leg, between Kuala Lumpur and Perth. Kuala Lumpur was also where BA009 changed crews. So the crew facing this emergency was relatively rested. There were 247 passengers and 15 crew on board the aircraft for this leg.

The flight crew departed Kuala Lumpur uneventfully, climbing to FL370 for their five-hour flight to Perth. As the forecast had predicted, the weather radar showed nothing that might trouble the crew. But just over two hours into the flight, the crew saw what looked like Saint Elmo’s fire outside the aircraft. This was at night. St Elmo’s fire is an electrical phenomenon, that usually means that there are storms nearby.

But the weather radar of flight BA009 stubbornly insisted that there was nothing to worry about. This is because these radars work by detecting moisture and water droplets. Some newer radars working on different wavelengths may detect small particles. But the weather radar that the pilots of this flight had in 1982, couldn’t.

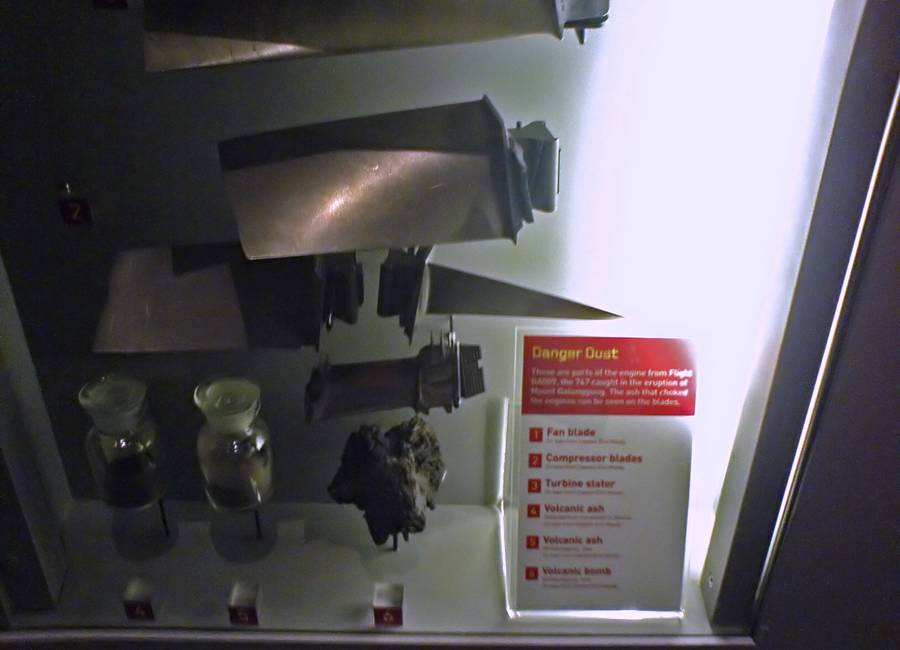

The crew didn’t know anything about a volcano near their route. This was because at the time it wasn’t normal for pilots to get detailed information about active volcanoes on their routes. The crew of BA009 switched on their engine anti-ice systems, as a precaution. But they didn’t know that tiny, sharp and very abrasive particles from Mount Galunggung volcano were now enveloping their 747.

Turning Into A Glider

During a toilet visit, the flight’s Captain had seen smoke seeping into the cabin through floor vents. But before he could figure out what this and the St. Elmo’s fire meant, engine No. 4 failed. Including a few seconds of disbelief, in the beginning, the crew took about 30 seconds to secure this engine. Then the other three engines also failed, one after the other.

Flight BA009 was now a glider. But the 747 still had electrical power, and the autopilot remained operational. The crew made a Mayday call, which was very difficult to get across. This was partly because of a language barrier and some non-standard calls. But beyond this, the electrically-charged environment around the aircraft hindered the radio signal.

The flight crew were over the ocean, south of Jakarta. So they turned around, to head back towards land. They immediately started trying to get their engines back on, although they were still at a high altitude. And they soon had to put on their oxygen masks, as the cabin was depressurizing. Initially, flight BA009 had to descend quickly, because the First Officer’s mask was in pieces.

Later the Captain slowed the descent when the First Officer managed to fix his mask. This is where the flight’s Captain made his now-legendary call to the passengers. He knew that the odds of surviving a ditching in the ocean, at night, with a 747, weren’t very good. But reaching land would also mean negotiating mountainous terrain, as the crew aimed to reach Jakarta beyond.

BA009 Can Climb Again! But Not Too Much

The crew never stopped trying to restart their engines. And as flight BA009 descended through 13,000 feet, engine No 4 roared back to life again. The crew then repeated their attempts with the other three engines, and they all appeared to work, once again. Relieved, the crew continued towards Jakarta.

The crew had immediately started to climb, in order to clear terrain between their aircraft and Jakarta. But as flight BA009 reached 15,000 feet, the St. Elmo’s fire once again began bathing the aircraft in its glow. As they levelled off at this altitude, engine No 2 began to vibrate violently. The crew decided to shut it down.

By now, the crew had suspected that this beautiful phenomenon had a connection with their plight. So they once again began descending, levelling off at 12,000 feet, continuing to Jakarta. The weather there was reasonably good, with no worries about visibility. But as BA009 approached the city, its crew realized that they had another serious problem.

They couldn’t see out! The tiny sharp bits of volcano ash hadn’t just overwhelmed the engines, they had also sandblasted the cockpit windows. Fortunately, the side windows were a bit better. Also, there was a narrow strip of less worn glass on the right side of the Captain’s windscreen. This would help when the British Airways crew would come in for their landing.

A Valuable Legacy

There were some additional challenges, with the landing in Jakarta (WIHH). The ILS was inoperative, so the crew had to fly a localizer approach. This required some coordination between the two pilots, with the first officer giving the Captain glideslope information. Flight BA009 landed safely, to the relief of everyone on board.

The crew would have one last problem, which was that they couldn’t really taxi. As soon as they turned towards the brightly-lit terminal, their sandblasted windows became opaque. They stopped, shut down their engines and waited for a tug to bring them in the rest of the way.

The aircraft in this event was a 747-236B, i.e. with Rolls-Royce RB211 engines and registration G-BDXH. At the time of flight BA009, it was called “City of Edinburgh”. British Airways kept it until October of 2001. In January 2002, it went to European Aircharter, who operated it for about two and a half years. It then went into storage, until it was finally scrapped in 2009.

It took some time for people to realize how important the lessons of this flight were. Just 19 days after flight BA009, another 747 had to shut down three engines for the same reason. And in 1989 a KLM 747 crew faced a nearly identical incident over Alaska. But forty years later, the amazing story of Captain Eric Moody, First Officer Roger Greaves and Flight Engineer Barry Townley-Freeman, is well known and credited with informing an entire industry.

For a MentourPilot video of this incredible adventure, see below:

1 comment

rippin

Great read…

Thank You

Be safe

Fish On…

Dave

>