A Transavia 737 crew started their takeoff roll on a taxiway, then aborted it and stopped safely. But how did this happen to begin with?

This incident happened on the 6th of September 2019. The Dutch Safety Board (DSB) released its final report on the event this week. It involves Transavia flight HV-1041, from Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (EHAM) in the Netherlands to Chania International (LGSA) in Greece. It is not clear who many passengers were on board. But this is a busy time of the year for flights between these two airports.

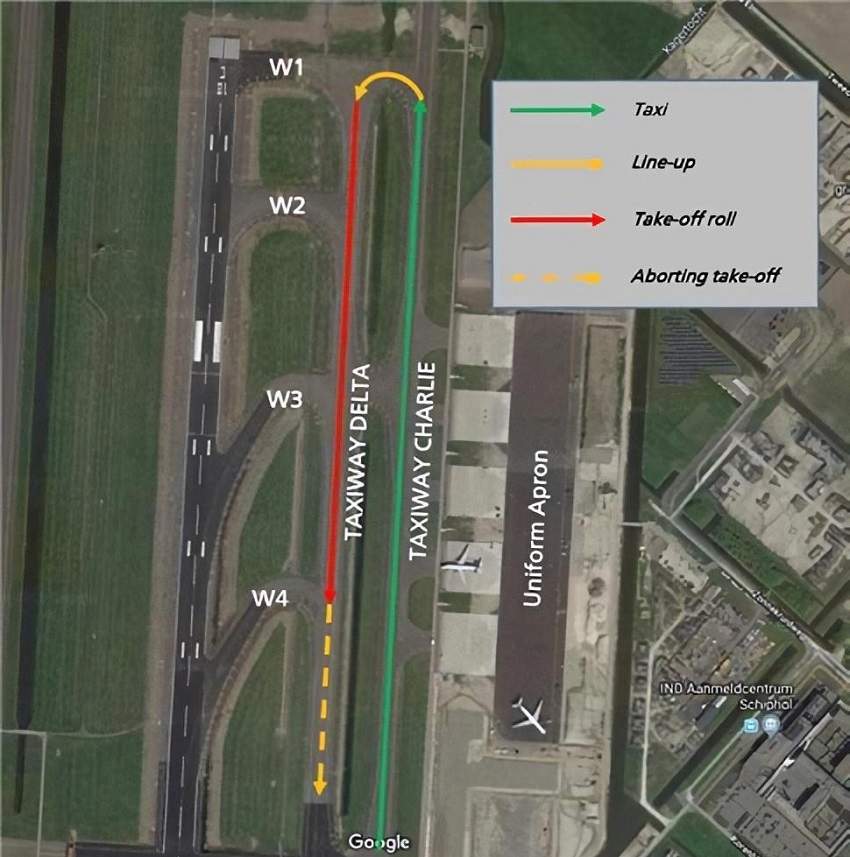

This was an early morning flight, in dark conditions. The flight was set to depart Schiphol airport using runway 18C. In their preparations, the pilots considered departing from further down the runway, to save on taxi time. The 737 Transavia crew had done a performance calculation for a takeoff after entering the runway using taxiway W3 (see below). But the flight was running on time, so there was little urgency involved.

There were no other aircraft taxiing in front of the aircraft. There are two parallel taxiways to the runway the crew would depart from. The one closest to the runway is taxiway D. The crew had instructions to taxi using taxiway C. Later, the Captain would remark that the centre line lights on taxiways C and D were not lit, except in the turns. Also, the 737 crew planned a rolling takeoff, not stopping as they moved from the connecting taxiway to the runway.

Some Confusion

The ground controller instructed the flight to contact the tower early. But the tower frequency was busy, so the crew couldn’t ask for departure using taxiway W3. However, the Captain then asked if they could depart from W2. The tower controller said that this would be a long detour, i.e. longer than going straight to the runway. This suggests that the 737 crew may have thought they were on a different taxiway (D) as they prepared for takeoff.

The crew would eventually get clearance to enter the runway and depart using W1. They made a left turn at the top (north end) of taxiway C, into connecting taxiway C1. But instead of then continuing straight for W1 and the runway, the 737 crew made a continuous left turn, lining up for takeoff with taxiway D.

From the right seat, the First Officer then applied takeoff thrust. The aircraft started accelerating, reaching 80 knots. Meanwhile, the ground controller who was talking to other aircraft on taxiway C, noticed (on ground radar) the 737 rolling for takeoff on taxiway D. He immediately informed the tower controller, who verified this. The tower controller then called on the aircraft to stop immediately.

This call to reject the takeoff came when the 737 was between W2 and W3, on taxiway D. The aircraft came to a stop just past W5. Incredibly, the two pilots did not realize what happened until after the controller told them. Fortunately, the aircraft did not require assistance due to hot brakes. The crew decided that they could proceed with their flight, after taxiing back to W1 and runway 18C.

737 Takeoff Roll On A Taxiway – The Aftermath

Normally, there are clues that should stop this from happening. The entry to the runway would have a flashing stop bar, marking its position. But the controller had switched it off, because the 737 crew had already gotten their takeoff clearance when they were further away, on taxiway C. Also, the air traffic controller did not realize that there was no continuous taxiway centreline lighting, between taxiway C and the stop bar at the end of W1.

The investigation into this event identified several factors. The taxiway markings and lights did not provide continuous guidance. Clearing the 737 crew for takeoff early, when they were still on taxiway C (i.e. not C1, after turning 90 degrees) robbed them of key cues. Also, ground controllers routinely used taxiways C and D interchangeably, for aircraft taxiing for departure using runway 18C. Finally, the controller did not monitor the aircraft after issuing the takeoff clearance.

Since the event, the airport authority made several changes. The first was to use taxiway D for departures from 18C, especially at night or during low visibility operations. Subsequently, the authority changed the markings on the taxiways, removing any ambiguity in the lines and lights.

Beyond its conclusions, the DSB investigation also noted that the continuation of the flight meant that CVR data was unavailable. Currently, most aircraft have CVRs (cockpit voice recorders) that save 2 hours of data. New EASA regulations (as of 1st of January 2022) call for CVRs to record 25 hours. But this applies only to new aircraft. The DSB would like to see such CVRs retrofitted to existing aircraft, as well.